“Thank you for your telegram. Yesterday I told your government how war can still be avoided. Although I asked for an explanation by noon today, so far my ambassador has not yet sent me any reply from your government. I am therefore forced to mobilise the army. An immediate positive and clear response from your government is the only way to prevent endless suffering. /…/ Willy”

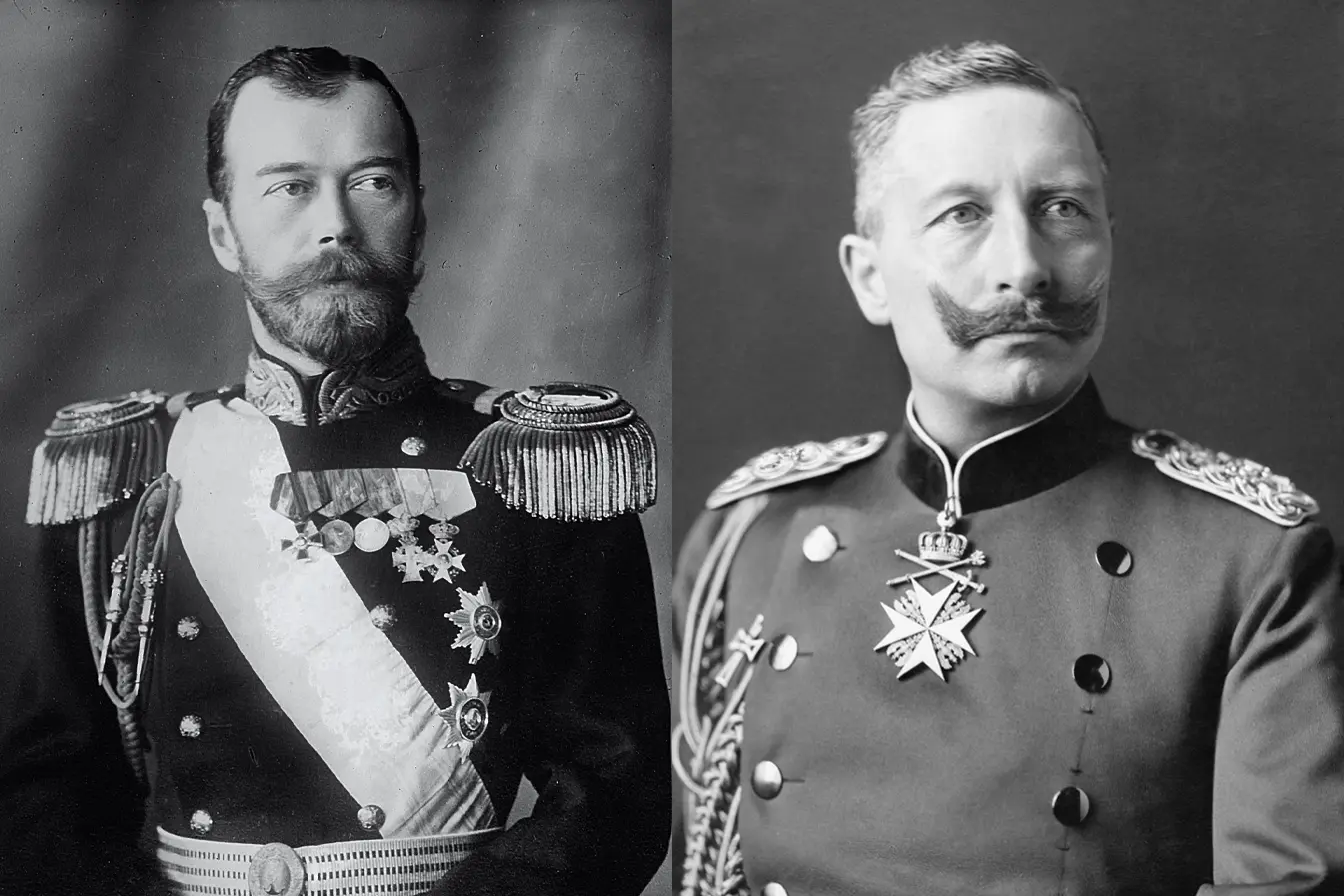

These were the last words of the German Emperor William II to his distant cousin Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia. It was 1 August 1914, the same day Germany declared war on Russia. In the three days before, William and Nicholas had exchanged a series of last-minute telegrams to prevent the then inevitable. William tried to prevent the mobilisation of the Russian army, while Nicholas begged him to stop the Austro-Hungarian offensive march on Serbia as a consequence – or rather an excuse – for not complying with the stern ultimatum after the assassination of the heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand. The Germans sided with Austria-Hungary and the Russians with Serbia, both pledging to stand by them in the event of armed conflict.

Although the sound of boots on the ground had been echoing louder and louder across Europe for several years, and war was only a matter of time away, the speed of events in the days leading up to the outbreak of war was astonishing. The scale of the conflict was also surprising, with at least ten countries involved within a few days and hopes that it was “just” a third Balkan war quickly dissipating.

How did this happen and where to look for the main culprits? To what extent and by whom could the war have been prevented in the first place? Could it have been Willy and Nicky? These and similar questions have occupied historians in particular for more than a century, and public opinion on important anniversaries.

Anyone who delves into the period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries will encounter one of its most distinctive features. This is the close kinship of European courts, which played an important role in international relations. Cousins, uncles, nephews, brothers-in-law, in-laws, all connected in one way or another to the grandmother of Europe, Queen Victoria of Great Britain, sat on thrones from Britain to Greece. Blood ties also meant that they tried to keep in touch with each other, under Victoria’s watchful eye, even if they often disliked or despised each other on a personal level.

Written correspondence was crucial for personal diplomacy between the royal families. And while most of it was dull and superficial, the correspondence between William and Nicholas had long-term consequences. Both were great-great-grandchildren of Tsar Paul I of Russia, and shared a common ancestor in King Frederick William III of Prussia. At the same time, William and Nicholas’s wife Alix were cousins and grandchildren of Victoria. They were also first cousins of the British King George V, who succeeded the late Edward VII in 1910.

The German Kaiser Wilhelm was a man of many faces, vain, arrogant, restless, suspicious and envious – today many believe he suffered from narcissistic personality disorder. Nicholas, on the other hand, was a calm, private, kind, but at the same time rigid, unimaginative and above all insecure ruler. What they had in common was an unwavering belief in autocratic rule and a divine right to the throne.

Despite their differences in character, they corresponded regularly at William’s instigation for twenty years, from 1894 until the fateful 1 August 1914. The correspondence consisted of letters and telegrams, the most famous of which is the series of telegrams written during the last three days before Germany and Russia entered the war.

Willy and Nicky, as they were diminutively addressed in accordance with the customs of European courts and especially of Victoria’s descendants, left a clear mark in their letters of their personalities, their relationships with each other and the social and political spirit of the times. They also played a role in the events leading up to the First World War, and the scheming William in particular, often unaware of the meaning of his words, regularly caused international outrage and disgust with his shamelessly incendiary rhetoric and aggressive military posture throughout his thirty-year reign.

But the web of circumstances leading up to the global carnage was simply too complex to assign blame in any one way. Their real power in foreign policy matters was also questionable. Nor do the last telegrams testify that William and Nicholas genuinely tried to prevent a conflict at decisive moments. But they were certainly not the peacemakers they liked to proclaim themselves to be. They were monarchs with an unwavering belief in their own importance.

Cousins on thrones

In the pre-war period, European countries were mostly kingdoms, including four of the Five Powers – Britain, Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary. Only France was a republic. Virtually all the thrones had at least one relative of Queen Victoria. In England, as a constitutional monarchy, the Crown had for centuries played a primarily ceremonial and representative role, so the wily Victoria compensated for her lack of political influence by carefully planning family policy.

The vast colonial empire also made the British monarchy the most visible, prestigious and wealthy, while Victoria and Albert also restored charm and respect to the royal family through their high moral standing. But they saw their offspring solely as instruments of dynastic wealth, not as individuals with their own needs and desires.

At the largest European royal gathering of all time, the funeral of Victoria’s son, King Edward VII of England, In 1910, seventy countries were represented in the procession, including the most important crowned heads: nine monarchs, all the relatives of the deceased (the King of England, the King of Greece, the King of Spain, the King of Belgium, the King of Norway, the King of Denmark, the King of Portugal, the Emperor of Bulgaria and the Emperor of Germany), and a host of heirs to the throne, princes, princesses, princes, princes, princes, princesses, counts and countesses, including representatives from other continents. On the surface at least, the late Victoria could have been proud of the success of her well-thought-out family project.

The parade was a surplus of glamour and the spirit of a time that was slowly but steadily running out of time. The message of power and influence that the monarchs were sending out to the world was in stark contrast to the demands of the impoverished masses for radical social change and the increasingly vocal left and liberal political elites. Royal family ties also proved largely irrelevant, as they failed to curb any attempt at democratic processes. The existence of autocratic regimes was called into question, and the war only accelerated these processes.

Moreover, the belief in friendship between nations, supposedly created by the intimacy between monarchies, was also an illusion. For several years after Edvard’s funeral, cousins who had spent their childhood holidays together on family estates and yachts, married their sisters and cousins, hunted together, gave each other glamorous titles and paraded to the masses in sumptuous uniforms, were on opposite sides of the bloody trenches of the First World War. At the end of the war, only a handful of them managed to hold on to their thrones, and among the great powers, only the British.

The sometimes different perspective of the process leading to the disintegration of the existing order is evident in the legacy of numerous personal documents, letters, diaries and photographs of some of the most important royal figures of the time. Correspondence, in particular, was a cornerstone of personal diplomacy and part of the family tradition that Victoria dutifully cultivated. Most of it was telegraphic, simple descriptions of events and family vicissitudes, but Victoria’s eldest grandson, King William II of Prussia and Emperor of Germany, true to his reputation as an unpredictable megalomaniac, also added a whole new dimension to written correspondence.

In his voluminous letters, he intertwined themes of friendship and family with the political, and his writing often bordered on the absurd. What came to light was his lack of understanding of the wider foreign policy context. He incited states against states, kings against kings, spread lies, especially if anyone dared to hurt his pride. He childishly denied true facts and events and even his own statements. This kind of behaviour was eerily similar to the behaviour of some of the world’s politicians on social networks today! He considered himself an expert in all fields, including giving the Norwegian composer Grieg advice on conducting and telling Richard Strauss that modern composition sucked.

He was very keen to give advice and opinions on subjects that did not concern him at all. “Your manifesto on the Duma has made a great impression in Europe – especially in my country, so please accept my warmest congratulations. This is a great step forward in your country and gives people the opportunity to make their hopes and wishes known to you /…/.”

So he wrote to Tsar Nicholas in 1905 after the massacre in front of the Winter Palace, when the Tsar’s army massacred a crowd of peaceful demonstrators and he was forced to promise reforms if he wanted to keep power.

Even William’s behaviour in his early youth suggested that he would one day be a difficult and unique ruler.

A decisive physical handicap

William II was born in January 1859 to Frederick III ‘Fritz’, heir to the throne of Prussia, and Princess Victoria ‘Vicky’, the eldest and most popular daughter of the British Royal Couple. The sweet baby was toasted all over Europe, but she was especially proud to be a grandmother who had secured another throne. Those were the days when memories of the victory over Napoleon were still vivid enough and the Anglo-Prussian alliance strong as a result. The English trusted the Germans much more than the French or the Russians. Moreover, both Queen Victoria’s mother and husband were of German origin.

It soon became apparent that Willy’s left arm was not as it should be, due to a difficult birth. Despite an army of doctors being called in, her nerves were permanently damaged and her arm was paralysed and shortened. The mother of the ‘crippled prince’, as his Prussian grandfather called him, did not accept this for many years, and the boy had to endure the tortures of hell as they tried to ‘fix’ him by very cruel methods. He stoically endured electric shocks, special stretchers, orthopaedic corsets, slashing of tendons and even dead rabbits – his arm was wrapped in their warm carcasses – and supposedly rarely cried.

At the same time, he was not allowed to let his disability hinder him in his preparations for his future role as ruler. He grew up like other children, and became even more enthusiastic about sporting activities. He became an excellent rider and swimmer and learned to shoot early on, fascinated by the army and navy. But he needed the help of servants all his life to dress and eat, and even special cutlery was made for him.

From the preserved photographs, young William in various military uniforms stares earnestly at the camera, always neatly groomed down to the smallest detail. He had a lifelong fascination with uniforms, and despite the difficulties he had in dressing due to his disability, he would change his clothes several times a day. The disability certainly affected his emotional development, but some even believe that the lack of oxygen at birth partially damaged his brain, causing emotional imbalance and hyperactivity.

When he was emperor, medical assessments from his youth came to light. They were not at all flattering, the Prince “will never be normal” and will be subject to “sudden outbursts of anger during which he will not be able to form a prudent or moderate opinion” and “although he is unlikely to go mad, some of his actions will be those of a man who is not quite himself”.

He was born in Prussia, the largest and most important German state, and when the united German Empire was created after the victory over France in 1871, the Prussian royal house of Hohenzollern became the Imperial House of Prussia and William became the second in line to the throne of the German Empire. Germany thus successfully joined the ranks of the European superpowers.

The Prussia of William’s childhood was an interesting hybrid between a scientifically advanced and culturally and intellectually enlightened society – where Goethe, Bach, Beethoven, the von Humboldt brothers, Leibniz, among others, created and explored – and the militant and autocratic ideology of the reactionary and aristocratic junkers, who were closer to their neighbours, the Russians, than to more advanced Western Europe.

William embodied these contradictions, and while he had anti-liberal military leanings, he regularly flirted with his mother’s and grandmother’s homeland and was jealous of its progress and prestige. He soon broke with his mother, who, as a conscious British woman, accused him of ‘Prussianism’ and arrogance. At the age of twelve, she described to Victoria her conceited, self-obsessed son, who was offended at the slightest criticism.

He was interested in everything, but only superficially, because he didn’t like hard work. He preferred to engage in long monologues, which his entourage patiently endured. Once, when a minister, who had to spend hours at his side, was finally allowed to return home, he first cursed aloud behind closed doors and then slept for twenty-four hours together. Although William could also be a charming and pleasant conversationalist, he was mostly just exhausting and exhausting to be around.

He married Augusta Victoria ‘Dona’, from another of the German royal families. She bore him six sons and one daughter, and gave him unconditional support and submission to his whims throughout her life. He even forced her to take slimming pills to stay thin. He found family life boring and preferred to wander the world. Of his children, he was attached only to his daughter.

It was quite different at the court of the future Russian Tsar of the Romanov dynasty, Nicholas II. William and Nicholas were so different that it is a miracle how long they managed to maintain friendly relations.

Shy Nicky in the family circle

Who hasn’t come across idyllic family photographs of the last Russian Tsar, his beautiful, melancholic wife and their five children, four statuesque Tsarinas dressed in white and the fragile youngest Tsarevich? The Romanovs lived in the golden days of Kodak cameras and were obsessed with taking photographs and editing family albums. Even with their extensive image material, their tragic fate still evokes chills and sympathy, as the innocent faces of the family members are forever etched in our collective consciousness. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, they became a very useful propaganda tool in the anti-communist struggle and were even declared saints by the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000.

But at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Tsar’s family was the embodiment of a universally loathed ruling class, unmindful of the masses, convinced that its mission was of divine origin. Living completely isolated from the real world, they took the devotion of their subjects for granted.

Nicholas was born in 1868 at the court of his father, Tsar Alexander III, and his mother, Princess Maria Feodorovna (née Dagmara) of Denmark, sister of the wife of the heir to the British throne and later King Edward VII. Thus, George V, who succeeded Edward in 1910, and Nicholas were first cousins. They looked so much alike that they were constantly confused with each other at family gatherings. They often spent holidays together at the court of their Danish grandfather, Christian, where they developed a close friendship and corresponded regularly.

While relations between the Russian and English monarchies were not the warmest, Victoria’s family ties meant that she still tolerated the Russian imperial family while despising their backward society. Elsewhere in Europe, with the exception of Germany, they also despised Tsarism. In closed Russia, however, they were suspicious of other countries, both Germany and England, even though the high circles were fascinated by English culture and tried to imitate it.

Nicholas was exclusively influenced by his autocratic father, who was in all respects anchored in the tradition of a closed, xenophobic and self-sufficient Russia, ruled by the Romanovs since 1613. The country covered one sixth of the earth’s surface and had a population of 120 million. But only 20% of them were literate, compared with over 90% in Britain.

He had a warm relationship with his parents, but they had little love for court and high society, so he grew up even more isolated than other royal children. He was a gentle, kind and polite boy who knew how to control his emotions in public from an early age. When he became Tsar, he mostly put on a mask of politeness and his interlocutors complained that they did not know what he was really thinking. But it was his kind, often dull eyes that made the biggest impression on everyone.

Like Germany, Russia was in a constant state of flux, with a growing part of society becoming Westernised and others clinging to the Russian tradition and romantically promoting Pan-Slavism. Next to the court, the Russian Orthodox Church was the most influential institution, more closely linked to the state than anywhere else. The Tsar had almost unlimited power and anyone who tried to promote progressive change became an enemy of the State and the Church.

Nicholas’s grandfather, Alexander II, did try to introduce some liberal reforms and made history, notably by abolishing serfdom in 1861. But ironically, he died in an assassination attempt and his successor, Nicholas’s father, once again stopped time and put an end to the experimentation with liberalism.

Nicky learned by watching his father, who tore up the constitution, introduced numerous anti-reforms, censored the media, ended the autonomy of the universities and rounded up dissidents. He had no real political education and was not allowed to read newspapers. It is understandable, therefore, that his picture of the world was completely distorted.

Nicholas courted his wife-to-be for a long time, and when she did agree to marry him, he was the happiest man in the world. He and the beautiful but melancholic and depression-prone Alexandra ‘Alix’ of Hesse-Darmstadt, by far Queen Victoria’s favourite granddaughter, had a harmonious and loving marriage. Nicholas was not a modern ruler, but he was certainly a modern and devoted family father and husband. He loved spending time with his children and his wife, reading Pushkin and Tolstoy to her in the evenings and sticking photographs together in the family album. But Alix showed signs of nervous illness and pathological discomfort with unfamiliar people and society from a very early age. Everything pointed to her having inherited the porphyria gene from Victoria.

Without a hair on your tongue

While Nicholas was struggling to cope with the fact that he would one day have to become Tsar, William could hardly wait to finally sit on the throne in 1888. He had convinced himself that he was the next Frederick the Great and therefore a capable politician, strategist, philosopher and soldier. At the beginning, he was adored by the crowds, because he loved to show off and made hundreds of speeches, he was young, charismatic and had boundless energy. He promised to transform the country for the 20th century. But he soon proved to be a reactionary and called Parliament a ‘pigsty’.

His words were rarely followed by action, and the young emperor was unable to distinguish the important from the trivial. He had a very high opinion of himself and surrounded himself with people who only fuelled this belief. He had to be photographed again and again, in uniform, surrounded by his six equally uniformed, tall, healthy sons, who together represented the values of old and new Germany at the same time. All but one of his sons later flirted with Nazism.

The family lived in a magnificent 650-room palace and William’s lifestyle was unashamedly extravagant. For example, he competed with his British relatives to see who had the bigger, better and more expensive yachts. Every year they competed in a yacht race.

He attracted attention everywhere and was written about all over Europe. He was so rare in Berlin that he was called ‘der Reisekaiser’ (the travelling emperor). His direct and often rude behaviour alienated most foreign monarchs, including his relatives. He once clapped King Ferdinand of Bulgaria on the buttocks and called him ‘Fernando nos’ because he was supposed to have a big nose. And he called the tiny King of Italy ‘Dwarf’ in public.

One of his most fateful moves was the dismissal of Bismarck. The Iron Chancellor, de facto ruler of Germany for three decades, who had made it the powerhouse of Europe and easily dominated William’s grandfather, had too much influence for William’s taste. There was no room for both. But it was widely believed in Europe that it was Bismarck’s policies that kept peace on the continent. After German reunification, he had fought tactfully and successfully against the Great Britain-France-Russia alliance, which would have threatened Germany. After his departure, it was Russia and France who forged an alliance, putting a ring around Germany.

The Emperor therefore quickly began to flirt with England, where they were receptive to closer relations, worried that William would lead Germany into Russia’s embrace. While he hated France consistently, he always had an ambivalent attitude towards England and Russia. When his more liberal period (1891-1895) came to an end, and when Germany too began to demand a “place in the sun” and with it a piece of the colonial cake, he distanced himself from England. Indeed, as the world’s largest colonial power, it was Germany that was most hindered in its hunt for new territories.

He increasingly turned to personal written diplomacy, for example by initiating a correspondence with Nicky’s father, Alexander III. After his death, he simply continued it with Nicholas. The thread running through it was undoubtedly hatred and incitement against England and his uncle Berti, then King Edward.

His letters to foreign monarchs caused many an awkward international situation, as he liked to promise impossible things. Criticism of his rule began to pour in from all quarters, encouraged from the sidelines by the still influential Bismarck through the press. German politics was becoming more chaotic by the day.

I’m not ready to be a tsar

Nicholas only started to learn about government affairs shortly before he became Tsar in 1896. It was all superfluous to him. “I cannot understand how anyone can read all these volumes of documents in a week. I usually pick out one or two of the most interesting ones, and the others end up in the fire.” He was desperate and admitted: “I am not ready to be a tsar. I never wanted to be. I don’t know anything about ruling.”

From the outset, it was obvious how out of touch with the people his rule would be. When thousands of people were trampled to death on the day of the coronation during a public celebration in honour of the young couple, Nicholas and Alix did not even know it and the celebrations continued with a grand dance. At that time, there was also a severe famine, which had killed at least half a million people, but Nicholas knew little about it, let alone took appropriate measures. Even the famous writer Tolstoy wrote to him about the desperate state of affairs and the misery, and urged him to adopt urgently needed reforms.

But he was more interested in the uniforms than in the uniforms. He considered himself to be frugal and had no idea how many millions of roubles it cost to maintain the Tsarist family.

The initial enthusiasm for the young and handsome Tsar faded as soon as it became clear that reform and liberalisation were definitely not on his agenda. Queen Victoria was also disappointed and corresponded regularly with her granddaughter Alix, as well as with Nicholas, in an attempt to keep the couple under control.

The couple were untouched by the growing social unrest and became increasingly withdrawn, moving from St Petersburg to Tsarskoe Selo, an elegant provincial royal town in a small town built by Catherine the Great. There, the Romanovs lived like in a fairy tale, convinced that they had a divine right to luxury. There were as many as 16,500 staff members at court, all of them constantly occupied with the trivial details of court etiquette. During meals, the Tsarina was dressed in the most precious jewels in the world, everything glittered with silver and gold and in general was unpleasantly reminiscent of Marie Antoinette’s court.

Outside their inner circle of ministers and advisers, the Romanovs rarely met anyone else. Because the Tsar was unable and unwilling to confront difficult subjects, the government and administration were without a firm hand and completely chaotic. Unlike William, the Tsar was a closed and private man and access to him was virtually impossible. This was compounded by the Tsarina, who had increasingly severe mental health problems and was constantly exhausted.

Their darkest side was undoubtedly their tormented relationship with Rasputin. The mystic of peasant roots from Siberia remains one of the most controversial Russian figures of all time. There are countless legends about him, but the fact is that he had a tremendous influence on the Tsarina in particular, as he was the only one able to alleviate the suffering and symptoms of the haemophiliac Tsarevich Aleksei.

Russians have always been mystics at heart and inclined to spiritualism, and the charismatic Rasputin easily won them over with spells, exorcisms and divination. This occult man undoubtedly had hypnotic powers, but his sexuality and primitive riots caused disgust and revulsion throughout the world. Alix never took another step without him, and he began to influence government affairs and the appointment of people to important positions. The Tsaritsa was increasingly hated and people enjoyed tarnishing her reputation with fabricated stories of orgies with Rasputin.

Even the Tsar was inclined to mysticism and, born on the day of Saint Job, was convinced that he too would face terrible trials. “God has willed it so” was the most common analysis of important events. This was also the case with the unexpected and heavy defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, which was the result of Russian expansion towards the Far East.

Even greater problems awaited the Tsar on his home doorstep. In January 1905, a peaceful demonstration in St Petersburg, demanding better working conditions and an elected assembly, turned into a ‘Bloody Sunday’, when military troops killed at least a thousand protesters. General strikes and uprisings spread across Russia and soon turned into a revolution, until the Tsar gave in against his will and promised elections and other reforms.

William’s policy through letters to Nicholas

Throughout these years, William corresponded diligently with Nicholas. After the Romanovs were assassinated in July 1918, a box containing, among other things, at least seventy of the Emperor’s letters to Nicholas was found and deposited in the state archives. An American journalist found the letters there a year later, and when they were first published in 1920, they caused a sensation. Written between 1894 and 1914, their correspondence ends with a series of short telegrams exchanged in the last days before the war, the swan song of the attempts to prevent war. These telegrams were published by the German government itself during the war in order to justify its own role in it.

The main content of William’s letters to Nicholas over the years was political. He ‘analysed’ international relations and gave his cousin advice on domestic and foreign political developments. These were times of colonial disputes and the struggle for ‘space under the sun’, during which Germany and Russia also occasionally competed for the same territories, especially in China. The Emperor could not contain his anger and wrote of Nicholas that he was ‘good (only) for living in the countryside and growing turnips’.

But even in his anger he did not last long, and soon he was happily writing to the Tsar again. He was goaded into war with Japan, which he described as a ‘yellow peril’, and racism flourished in Nicholas’s vocabulary – the Japanese were ‘little monkeys with short tails’. For two Japanese soldiers, he was to need only one Russian. But he was sorely mistaken. Defeat in the war with Japan was just another step on the road to the inevitable end of the 300-year dynasty.

William also analysed at length the Russian Revolution of 1905 and advised Nicholas on how to approach the people. His favourite, however, was to turn to England and France, trying to lead Nicholas away from an alliance with them. He regularly sent him articles from the English newspapers, proving that the British had been supporting the Japanese and their mobilisation since 1903. He also regularly spat at the French in an attempt to cool the Russo-French alliance, but he failed.

At times he was so intrusive that the otherwise calm and polite Nicholas wrote in his diary about the annoying Emperor, with whom he would have liked to cut off all contact. Even his cousin Alix disliked him, although he mentioned her in every letter. But Nicholas’s ministers thought that good relations with Germany were important and encouraged him to be friends. When a Russian was once forced to give a German the title of Russian Admiral, he later issued the words, “To vomit!” They met on several occasions and the letters show what was discussed at these meetings.

For example, they met secretly in July 1905 in Björkö, Sweden, to conclude a Russo-German treaty on mutual military and commercial assistance. They wanted to show that they were important: “24 July 1905 is a cornerstone of European politics and turns over a new leaf in the history of Europe”, William wrote to Nicholas.

When their ministers found out what was happening, they were horrified and scolded them like little children. Of course, nothing came of the project, not least because Russia was already allied with France, which would have had to agree to a German-Russian alliance. But the Germans and the French had been mortal enemies since 1871, and the French, in particular, never forgave them for taking Alsace and Lorraine.

On the brink of war

Even without William’s incitement and undiplomatic behaviour, Europe was boiling and many smaller, localised clashes were steadily multiplying. This caused widespread paranoia and mass armaments. Military authorities gained influence and often adopted an aggressive militant posture, encouraging entry into the war. Germany was the most obvious example – there the civil authorities, as well as the Kaiser, were marginalised.

The Austrian General Staff was also on alert, because the greatest unrest was in their neighbourhood, in the Balkans. After two Balkan wars (1912-1913), so many problems remained unsolved that a third was only a matter of time. With the Ottoman Empire growing weaker and weaker, everyone hoped for territorial gains and strategic influence in the Balkans.

But on the royal calendars, 1913 was a year of anniversaries and celebrations, accompanied by pomp and extravagance on an unbelievable scale. The twenty-fifth anniversary of the reign of Emperor William, the tercentenary of the Romanov dynasty, the centenary of the victory over Napoleon at Leibnitz, the marriage of William’s only daughter – these were the events that cut short the time of the crowned heads of Germany and Russia.

After a long time, the Tsarist couple reappeared on the streets of Russia and people were delighted. Nikolai and Alix were naively convinced that they were adored. It was just a facade, people were curious and hungry for entertainment. But they were increasingly dissatisfied with the regime and between 1912 and 1914 there were nine thousand strikes!

And then the Sarajevo assassination happened and countries started sending each other telegrams of ultimatums overnight. The Serbs were given an incredibly harsh ultimatum by Austria-Hungary, which even with the best will they could not fully comply with. The Russians, in Slavic solidarity and hoping for access to the Dardanelles, stood up for them, which, because of the Russo-French alliance, drew the French into the conflict.

The Germans similarly sided with the Austrians. The German military elite saw the murder as an opportunity for war. William was not enthusiastic about it, but he was furious about the assassination of the heir to the throne, and saw it above all as an attack on the institution of an autocratic ruler such as himself. He blamed Nicholas for coming to the defence of the murderers of a member of the royal family. But all were convinced that the confrontation, if it came to that, would be short-lived.

These were the outlines of a wider context when, on 28 July, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. There was little time for a diplomatic solution. But it was Tsar Nicholas and Emperor William who felt called to try. On the morning of 29 July, in an attempt to prevent a confrontation, they began an intensive exchange of telegrams in an attempt to influence each other’s fateful decisions. Nikolai urged the Germans to stop the Austrians, while William wanted to prevent the Russian mobilisation. The first telegram was sent by Nicky early in the morning of 29 July.

Failed telegram diplomacy

“At this serious moment, I call on you to help me. A shameful war has been declared against a weak country. The indignation in Russia, which I fully share, is enormous. I foresee that in the very near future I will be under severe pressure to take extreme measures that will lead to war. In order to prevent such a catastrophe as a European war, I implore you, in the name of our long-standing friendship, to do everything in your power to stop your ally before it goes too far. Nicky”

In his reply, William, while agreeing with mediation and the desire to preserve peace at all costs, showed understanding for Austria and disgust with Serbia. He urged Russia to stay out of the conflict, to hold bilateral talks with Austria and, above all, to refrain from military action. The same day, in a new telegram, Nicholas suggested that the Austrian-Serbian dispute be settled by a Hague conference, but he never received a direct reply.

This is why many historians who wanted to blame Wilhelm for the war have seen the lack of German consent to convene the Hague Conference as proof. But more than William, it was the fault of the German military elite, which was indeed looking for every possible excuse to start the conflict. On the other hand, Nicholas really tried to do everything he could not to provoke Germany too much. He was terribly afraid of having to take his country to war.

In the following days, under pressure from both governments, the friendly tone of the correspondence cooled more and more, and conflicting views within the camps also came to light. William, under the influence of the Chancellor, told Nicholas: “/…/ if Russia mobilises for an attack against Austria-Hungary, my role as mediator, which I have assumed at your request, will be compromised, if not impossible. The whole weight of the decision now rests on your shoulders and you will have to take responsibility for war or peace. Willy”

The Tsar turned completely pale and almost choked as he spoke. The situation was tragic for him. He was aware of the burden of responsibility, even though all the generals had advised him to order a general mobilisation. “Just think of the responsibility you are putting on me. Remember, it is a question of sending thousands and thousands of men to certain death.”

On July 31, tensions escalated and neither side relented enough, the Russians refused to stop military preparations and the Germans stubbornly supported all Austrian actions. The Tsar swore that mobilisation did not mean war, but the Germans did not believe him.

The then French ambassador to the Russian court, Maurice Paléologue, described in detail the events of the last hours before Germany and Russia entered the war in his diary. At eleven o’clock on the evening of 31 July, the German Ambassador Pourtalès arrived at the Russian Foreign Ministry, visibly shaken, and delivered an ultimatum to the Russian Foreign Minister Sazonov – if Russia did not stop mobilising within twelve hours, Germany would mobilise its troops too.

Nicholas made another conciliatory attempt with William: “I understand that you want to mobilise, but I want your assurance, as I have given it to you, that these measures do not mean war and that we will continue to negotiate in order to save the peace that is so precious to us. With God’s help, our long and tested friendship could prevent bloodshed. I await your reply with confidence. Nicky” It was in vain.

On the evening of the first of August, Ambassador Pourtalès returned to the ministry and, with his eyes downcast, handed Sazonov the declaration of war, which ended with the theatrical phrase: “His Imperial Highness, my all-powerful sovereign, in the name of the Empire, accepts the challenge and declares a state of war with Russia.” Pourtalès clung to the window and began to weep inconsolably.

Responsible but not guilty

Willy and Nicky failed. No one can blame them for not having made a last-minute effort to prevent the entry into the war. But they had paved the way for it many years before, and both of them, and especially Willy, should have accepted the responsibility they bore in aggravating international relations. Reckless diplomacy, armaments, colonial appetites, right-wing politics and militarism, they were guilty of it all. As the highest representatives of their countries, they should have played a much more positive role, instead of seeing themselves as gods.

Europe went to war in a patriotic fervour. There were no protests, and men volunteered in large numbers. William and Nicholas at first deluded themselves that they were useful, but soon became irrelevant. In their shiny uniforms, they walked around the headquarters, nodding, pinning medals and inspecting the troops.

The turmoil and defeats they have witnessed have broken them. William was depressed and Nicholas apathetic and drained. His eyes were those of a man resigned to the inevitable. In the revolutionary year of 1917 he was forced to abdicate the throne, and the following year he and his family were executed in a criminal manner by the Bolsheviks with bayonets and rifles. Few mourned them.

William would almost have suffered a similar fate, but after his abdication he was given refuge in the Netherlands, where he lived until 1941, away from the eyes of the public he loved so much. He even discussed with the Nazis the possibility of restoring the throne and the title of Emperor. When the Germans invaded Paris, he sent congratulatory messages to Hitler. As his mother had said, disappointedly, decades earlier, “The boy does not know how to learn from his mistakes”.