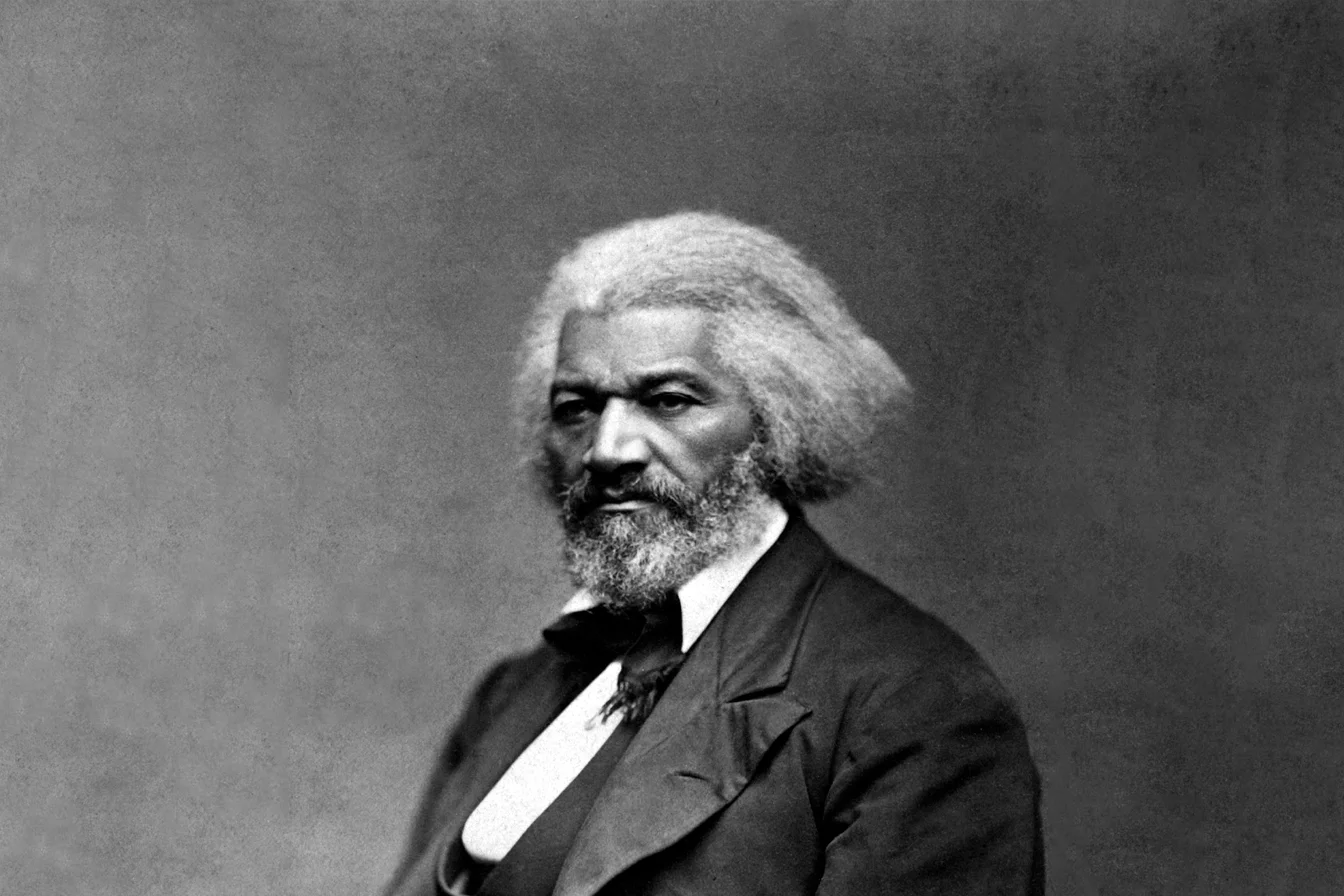

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey (Frederick Douglass). This was the name given by Harriet Bailey, a black woman on a plantation in the middle of Maryland around 1818, to her son, who would go down in the history of the struggle to abolish slavery as Frederick Douglass. An escaped slave and the most famous black American of the 19th century, Douglass, first through his personal story and then as one of the leading abolitionists, helped to make the issue of racial equality central to the social fabric and common future of the young union of American states. The issue, which still divides the United States today, has perhaps the deepest impact of any issue on American society, and, as the root cause of the Civil War, was also the only one that almost caused the break-up of the American state in its less than 250-year history.

Douglass, writer, orator, newspaper editor and publisher, diplomat and politician, and above all a champion of human rights and the emancipation of African Americans, described the grim truth of the slave’s daily life with such authenticity, detail and poignancy, based on personal experience, that few could remain indifferent. Like thousands of others, he was born to a slave mother and an unnamed white father, in all likelihood her owner. Like thousands of others, his human dignity was trampled upon at an early age. And like thousands of others, white and black, he felt such a strong revulsion against the institution of slavery that he dedicated his life to fighting it.

Of all the campaigners for the abolition of slavery, Douglass was one of the most influential and certainly the most charismatic. He gained fame as one of the few black Americans who, after escaping from slavery, masterfully put his experiences into an autobiography, thus beginning to demolish the myth of the intellectually inferior, unskilled and illiterate slave. Whites justified slavery as, among other things, a system that was beneficial and good for blacks, allowing them to earn a decent living, which they themselves would not have been able to do because of their natural inferiority.

He understood very well the power of his personal phenomenon and used it skilfully to win supporters in the struggle against slavery and later to equalise the civil rights of white and black Americans. He was the most photographed American personality of the 19th century and even more famous than Abraham Lincoln himself, before the latter became President of the United States, who of course went down in history as the liberator of the slaves. Lincoln said that Douglass was the man whose opinion he valued most in the country.

Young Frederick, through a series of happy accidents, learned to read and write during his otherwise typical upbringing as a slave boy. This was the first and perhaps the most important turning point of his life – understanding and mastering the written word opened the door to a world of intellectual freedom. Thus, when he realised that freedom of mind and spirit was a given, even for the most humble man, he vowed to free himself from the physical shackles of slavery. Along the way, he helped other slaves, while at the same time spreading awareness of the necessity of racial equality for the future of mankind and the evils embodied in the slave system through active political participation, writing and high-profile speeches.

Slave ownership was the foundation of the American state

Enslavement has been with humanity since the dawn of civilisation. Aristotle, with his so-called climatological theory, was the first to make an ideological case for Greek superiority and its slave-owning practices. Extreme climatic conditions were supposed to make blacks mentally, physically and morally less developed, incapable of self-government, progress and understanding of the concept of freedom. “Burnt faces” was Aristotle’s term for Africans, and the Greeks were supposed to be the most beautiful and capable rulers. He wrote: “Mankind is divided into masters and slaves, or, if you like, Greeks and barbarians, that is to say, those who have the right to rule and those who are born to obey.” This was the belief of all slave-owning societies up to the modern era, justifying their behaviour as necessary and socially profitable.

The enslavement of Africans was natural, normal and sacred, and the first global enslavers and international slave traders were the Muslims who decimated sub-Saharan Africa in the Middle Ages. When the Portuguese and later the Spanish began their conquest of Africa, they quickly learnt this ‘trade’. And when they ventured further afield, to South and Central America, colonialism and imperialism flourished. From the 15th century onwards, slavery provided an easy way of obtaining cheap labour to cultivate vast, newly conquered territories. The slave trade quickly became one of the most profitable businesses.

Colonialism brought enormous economic benefits and therefore soon became a status symbol. The English, like all influential European nations, joined the colonial race. They soon began to settle the area of the future USA in large numbers and the tobacco, cotton, sugar and rice plantations in the South required many labourers. So all the stage was set for the emergence of one of the most inhuman, exploitative and altogether ignoble social systems of all time, American slavery.

Early Christian theologians argued that the human hierarchy is natural because it is dictated by God. And it was their teachings and Aristotle’s tradition that were adopted by the deeply religious Puritans, who were among the first settlers in North America and who successfully brought established racial ideas across the ocean from England in the early 17th century. Slavery was accepted in America from 1619, when the first cargo of slaves arrived in Virginia, and by the time it was abolished in 1865, as many as five million slaves had been brought from Africa to America. The institution of slavery was therefore in the very fabric of the young American state and was so taken for granted at the birth of Frederick Douglass two hundred years later that even those who opposed it simply accepted it and did not have much hope that it would ever be abolished.

The United States of America has always been divided into North and South along social, political and climatic lines; in the North there were the so-called free states with less intensive agriculture, manufacturing and shipbuilding, while in the South slave-based agriculture was the driving force of economic development and an integral part of the culture. The richest landowners were those who grew cotton and exported it to England, the cradle of the textile industry. Large plantations thus needed many hands. The difference was also increasingly evident in the cultural and religious organisations – while the North was more progressive, the agrarian South was characterised by a conservative view of society.

The first major North-South split on slavery occurred at the founding convention in Philadelphia in 1787, when it was the hottest topic. After lengthy debates, the Southern states threatened not to join the new country if slavery was threatened. Thus, despite the ideals of the American Revolution, economic interests prevailed and slavery was enshrined in the American Constitution, which defined slaves as property. At least the opponents succeeded in securing a ban on the international slave trade only in 1808.

The South began to fall further and further behind the North, which was not dependent on agricultural activities, and progress was based on free labour, which illiterate slaves struggled to cope with. At the same time, slavery was increasingly hard on the American conscience. It was abolished in most northern states anyway, for example in Vermont as early as 1777, and there was a growing international movement to abolish it. The North-South divide grew slowly in the run-up to the Civil War, and anti-slavery movements in the North grew more numerous and vocal. The accounts of escaped slaves like Douglass became their manifesto.

Frederick Douglass had a harsh realisation – I am a slave

Until the age of six, Frederick Douglass grew up unencumbered in the loving atmosphere of his grandmother’s hut, unaware of his status as a slave. As young slave children were unfit for work, it was customary for the first few years for them to be brought up by older female relatives while their mothers toiled on distant plantations. They rarely, if ever, saw their children. Even Frederick had only vague memories of his mother – sometimes she would walk twenty kilometres at night after work to hug him in his sleep and then return to the plantation before sunrise. A minute late for work could mean a whipping, a beating, a spanking, a spell in irons or starvation. Many years after his mother’s death, Douglass was proud to learn that Harriet was the only slave around who could read.

The truth was usually kept from the children of slaves as long as possible by their relatives, to give them at least a few years of a carefree childhood. So the day the grandmother handed over little Frederick to the owner without a word, at the owner’s behest, it came as an indescribable shock to him. It was time for his mission as a slave. Despite finding himself among older brothers, sisters and cousins with whom he shared a destiny, his life was turned upside down and he quickly learned what it meant to be a slave. He lived on a huge plantation estate with more than a thousand slaves, owned by one of the wealthiest families in Maryland, and employed by its owner.

He witnessed daily exploitation, humiliation and physical violence against slaves. His first owner, Master Anthony, felt a special satisfaction, if not a thrill, in their abuse. Frederick was often awakened in the morning by the horrific screams of his aunt Hester, barely 15 years old, whom Anthony whipped to the point of madness, tied to a post – her back was a bloody shithole and “where the blood ran harder, he beat harder”. Nothing but fatigue could make the brute stop whipping. Douglass later wrote: “As long as I live I shall not forget it. It hit me with terrible force. Through the blood-stained door I entered the hell of slavery. The spectacle was ominous and I wish I could have put on paper the feelings that overwhelmed me.”

The conditions on the plantation were typical of the American South. Slaves were divided into domestic and field workers, some of whom also learned the various trades needed to maintain such a large estate. They were more valued and worth more. For example, newborn babies cost $300, teenage girls $1500, and skilled craftsmen up to $2500. The cost of maintaining slaves was quite small, with only a few items of clothing and a pair of shoes a year, and children under the age of ten were only entitled to one knee-length linen shirt. Mortality was very high due to poor hygiene conditions, especially among children, who contracted pneumonia, malaria and tetanus.

At that time, the South was home to around 12 million people, 4 million of whom were slaves. But only a very small percentage of families had more than fifty slaves. The status of a child was legally determined by the mother, allowing white landowners to afford unlimited sexual exploitation of slaves. The number of mulatto children grew rapidly.

Douglass was probably really the owner’s son, and that’s why he took it quite well as a child. As he himself wrote, he did not suffer much except hunger and cold, and he was not beaten. Being a bright boy, he won the affection of the owner’s daughter, who at the age of eight sent him out of the country to the city of Baltimore, where he was to take care of the young son of Anthony’s relatives as a house slave. He thus escaped the hardships of plantation life before it had begun in earnest.

Knowledge is power – the path to freedom

Frederick’s new mistress was gentle, tender and often motherly towards him. Having never owned a slave before, coming from a poor working-class family, she was not used to the socially accepted norms for the treatment of slaves. She treated him as a human being, even as her own child, and not as material property. She also recognised his talent and wished for him not to remain ignorant. She taught him to read and read him passages from the Bible every day. Who would have thought that by opening the door to literacy for a young boy, young Sophia Auld would not only change the course of his life, but also accelerate the course of black emancipation history?

But it was a crime to teach slaves to read and write. As Sophie’s husband said when he found out about his wife’s actions a year later, “If you give a murderer the finger, he will take your hand. All a bastard needs to know is that he must obey his master. Learning will bring out the best bastard in the world. If you teach him to read, you will no longer be able to keep him, because he will no longer want to be a slave.” This was Douglass’s first life lesson in anti-slavery. And not only did he remember it well himself, but with a distinctive gift for oratory, he passionately disseminated it for the rest of his tumultuous and eventful life through hundreds of speeches devoted to racial polemics and the slavery question.

Despite the fact that his first lessons ended so ingloriously, Douglass quickly became self-taught, devouring the written word wherever he could. He would give poor white boys his lunch or the few coins he earned for errands, and in return they would give him worn-out notebooks, books and newspapers. At the age of twelve, he was already interested in political subjects, and his ideological opposition to slavery began to take shape through reading.

The first book he bought for himself was called The Columbian Orator, a then very popular and widely read collection of the most influential speeches, essays and lessons in oratory from the ancient days of Socrates and Cicero to the modern Milton and Washington. The texts dealt with themes of freedom, democracy, courage and human rights, but Douglass was most impressed by the Dialogue between Master and Slave. In it, after a failed escape attempt, the slave explains to the master the meaning of the act and justifies the slaves’ right to freedom, thus engaging them in a debate on the essence of slavery. In the end, the master realises how mistaken he was in his belief in the justice of slave-owning relations and frees the slave.

Douglass thus learned not only how to read, but above all how to argue well. At the same time, somewhere in the middle of Illinois, another self-made man and then a clerk in a general merchandise store, Abraham Lincoln, was reading the same book, and he too had a childhood appreciation of the word and a love of a good debate. Both of these two giants of the struggle against slavery were therefore aware of the importance of speech as a means of persuasion.

Life as an urban slave gave Douglass much more freedom of movement and leisure, and he soon began to literate other slaves. “Once you learn to read, you will be free forever,” he told them. He was becoming increasingly influential among his fellow slaves, but to the whites he was an agitator and, as such, too dangerous. Soon he was sent back to the country to “break me as they broke animals to make them submit”, to be hired out to the notorious “slave-breaker” Edward Covey, famous for taming even the most rebellious and wilful slave.

Not Frederick! After a few months of beatings, when Covey again attacked him with his fists for no reason, the teenager fought back and they brawled until Covey passed out. Although Douglass could have been legally sentenced to death for this act, the only consequence of his courageous resistance was that the humiliated Covey never physically confronted him again. But for Douglass, the incident was still a straw in the rough and the decision to escape was finally ripe.

He planned his first escape with a group of friends, but it ended in failure after one of them betrayed the others. They were imprisoned and the slaves, especially Douglass as the leader of the fugitives, were convinced that they would at least be sold and displaced, if not hanged. But the men were lucky and all were returned to their owners. But Douglass, whose name was now known to all the local white landlords, was no longer safe in the country, because the whites wanted to get rid of him by any means necessary. They called for a lynching as the best solution to the problem of the “too clever” slave, who had already provoked them with his well-attended slave lessons before trying to escape.

After the organised violent uprising of Virginia slave leader Nat Turner a few years earlier, Southern planters were still in constant fear of a re-mobilisation of slaves. The deeply religious Nat Turner believed that his divine mission was the liberation of the black race and he and his followers massacred 60 whites in a few days. This uprising had a lasting impact on the consciousness of black people, who have since come to believe that collective resistance is possible and may one day even succeed.

Douglass also believed in the ultimate emancipation of all slaves in one way or another, and the hope of a better tomorrow for blacks was with him throughout his life’s endeavours. But first he had to save himself. He was planning his second escape in Baltimore when, for his own safety, he was returned to the home of Thomas and Sophie Auld. Apparently, his owners had always recognised something special in him that set him apart from the others and had often granted him privileges that other slaves did not enjoy. So now in Baltimore he was freer than ever, learning a trade in shipbuilding and even able to find his own work, live on his own and move about freely, on condition that he handed over his wages to his owner at the end of the week.

Frederick Douglass, then still Bailey, was increasingly alert to the activities of the various anti-slavery societies and was the first to hear of abolitionism and the abolitionist movement. At one of these meetings he met his future wife, Anna Murray, a free black woman. Anna helped him to finally escape; she disguised him as a sailor, he borrowed an acquaintance’s identity papers and wrote a travel pass. Within 24 hours, he was free. In New York State, where slavery was outlawed.

To avoid arrest, he had to change his name, and in 1838 the world got Frederick Douglass. He and Anne moved to Massachusetts, a progressive centre of the abolitionist movement with a large community of free blacks, a developed shipbuilding industry and enough jobs for the young couple.

New Life – a showcase of slavery

Despite, or perhaps because of, the challenges of a life of freedom and the constant racial discrimination and segregation Douglass faced in his search for work and while working, he found time for social and political engagement. He subscribed to the well-known abolitionist weekly The Liberator, which called for the immediate abolition of slavery and the granting of equal rights to all people. It was banned in the South and there was even a reward for the arrest of its editor, the famous William Lloyd Garrison. For Frederick, however, the paper was “… food and drink. My soul was as if on fire.”

He attended anti-slavery rallies, at first as an observer, but soon he spoke out about his experiences. He was used to speaking to what he called his “black brothers” as a confident and forceful speaker, but the first time he spoke to a large, predominantly white audience – at a Massachusetts anti-slavery rally in Nantucket – his voice was shaky and his words slurred. “I still felt like a slave, and the thought of speaking to white people weighed on me.”

The audience held its breath until the end of his passionate and impassioned speech, and the white abolitionists, especially their leader, Garrison, immediately recognised in him a great orator and an advertising opportunity for the movement. He had a natural magnetism and added just the right amount of humour, sarcasm and pathos to the vivid descriptions of his slave years to make the audience laugh and cry at the same moment.

He began to travel around the country, addressing both organised anti-slavery rallies and spontaneous crowds in churches, schools, parks and barns wherever the opportunity arose. He was paid a living wage for his speeches.

The phenomenon of Frederick Douglass, a strapping, brave, confident and, above all, extremely talented young man, spread rapidly in abolitionist circles in the North and became and remains a symbol of emancipation for black people. With a polished and learned manner, he fairly shook the generally accepted prejudices of the inferiority of the black race.

It was his obvious intellect that led doubters to publicly accuse him of being a fraud and of never having been a slave in the first place. Even his supporters often advised him before his appearances to add a little “plantation sound” to his “too white” accent for credibility! Of course, such advice was racist from today’s point of view, as Douglass was aware, but the prevailing opinion among all whites, not only slave-owners and slavery advocates, was that blacks were inferior and as such did not belong in an overly “white” behaviour. Even he himself wrote: “I did not look like a slave, nor did I act like one or talk like one.”

To silence the critics who did not believe him, he soon published his first autobiography, The Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave – written by himself. It reads like a suspense novel and became an instant literary bestseller, bringing Douglass international fame. In the first year after its publication, 30,000 copies were sold. He diligently added to his life story and wrote three more by the end of his life.

He was not the only one famous for his so-called slave literature, but his narrative was original and authentic. Most accounts of slave life at the time were written by white authors who, while committed to the abolition of slavery, often harbored deep-seated prejudices about the inferiority of the black race. For example, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, while condemning slavery, also portrayed black people as good, spiritual and simple people who deserved to be free as such. Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Douglass’s first autobiography, while presenting a different view of black people, were decisive in raising the profile of the race issue in the wider public.

By publishing the detailed events of his life as a slave, with names of white men, descriptions of events and places, Douglass revealed his identity and the likelihood of his being caught and returned to his owner was high, even though the book was banned in the South. Indeed, under the strict Fugitive Slave Law, “slave catchers” had the right to catch fugitives even in free states and return them to the South. Fearing exposure, his friends sent him on a lecture tour of England, Scotland and Ireland as a member of the anti-slavery movement.

Life mission

He was enthusiastically welcomed there, as slavery was seen as a shameful relic of the past, and Douglass successfully gathered supporters to put international pressure on the US. But what marked him most was the respect and sense of equality he received – for the first time in his life, he was not barred from hotels, thrown out of first class on trains, humiliated, physically harassed and abused because of the colour of his skin. Whereas in America a slave could be hit in the lottery and horse races, or given to a child as a birthday present, in England black people were given the same rights as white people.

For a while Douglass even toyed with the idea of moving to England with his family – leaving behind a young wife and four young children whose future he was worried about – but as a patriot he felt called to fight against slavery in his native land. English abolitionists raised the money to formally buy him back, and after paying $710.96 to the owner, Thomas Auld, he returned home a free man.

Now a distinguished and internationally renowned lecturer and author, he set out to publish his own newspaper, whose motto was “Justice has no gender – Truth has no colour – God is the Father of us all and we are all brothers.” The Northwoman, as the weekly was called after the star by which slaves on the run from the South to the North were oriented, was just one of Douglass’s initiatives in the turbulent decade before the Civil War. Even Charles Dickens collaborated with him, publishing in the paper extracts from his famous novel Bleak House.

Douglass also touched on general equality issues, such as the rights of indigenous Indians, and women’s rights in particular. He was a lifelong supporter of women’s rights and was one of the few men to attend the first mass women’s convention in Seneca Falls in 1848. He gained such a strong reputation among women suffrage fighters that later, when Victoria Woodhall, an eccentric American suffragist, was the first woman to run for the US presidency in 1872, she nominated him as her vice-presidential candidate without his knowledge.

But it was not only his social engagement that stirred spirits, but also his private life. He became very attached to the activist Julia Griffiths, who became his closest collaborator and even moved into the Douglass home for a few years. Julia was white and she and Douglass were often seen on long walks, deep in conversation. Whether they had more in common than intellectual attraction has never been proven, but it was obvious that his wife Anna was not his intellectual equal. She remained illiterate all her life and never took any particular interest in his work, but her main concern was for her home and children. Nevertheless, they lived together and he was deeply saddened by her death from a stroke. When he remarried two years later, to Helen Pitts, a white woman twenty years his junior, the public uproar was again intense. But such was the personality of Frederick Douglass, no one was ever indifferent to it.

And it was the same during his speeches. In 1852, when he was invited to give a speech to mark the 4th of July, the most important holiday for Americans to commemorate the signing of the Declaration of Independence, he gave his most famous and, for some, most important abolitionist speech of all time, What Does the Fourth of July Mean to a Slave? The speech was a protest against racial discrimination and inequality, and a graphic demonstration of the duplicity of the American state, which, on the one hand, extolled its greatness and the values of liberty and equality on which it was founded, while, on the other hand, shamelessly continued to support and defend slavery.

“What does the 4th of July mean to an American slave? I tell you, this day reveals to him even more than other days of the year that he is the victim of gross injustice and cruelty. To him, your celebration is a mere fraud … your national greatness, an inflated conceit; your joy is empty and heartless; your shouts of liberty and equality are a hollow lie; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings … are to him a deception, a disappointment, a blasphemy and a hyprocrisy – a veil that covers crimes that would shame even savages. Do you want me to tell you that man has the right to freedom? That he is the owner of his body? /…/ There is not a man in this world who does not know that slavery is unjust for him. /…/ We need a storm, a tempest and an earthquake. We need to awaken the national consciousness, to shake its decency, to expose its duplicity and to denounce its crimes against God and man. “

His home was one of the stops on what was known as the Underground Railway, a group of safe houses through which escaped slaves travelled to freedom. The most famous “conductor” was Douglass’s close friend, the intrepid Harriet Tubman, also an escaped slave from Maryland, who rescued at least three hundred slaves. Often, Douglass would return home in the evenings to find a pair of frightened souls on their way to freedom.

Both Douglass and Tubman were also friends with the radical and militant anti-slavery activist, the white John Brown. The latter believed that the abolition of slavery could only be achieved through armed insurrection, and in 1859 he was the instigator of the infamous attack on the Harpers Ferry armoury. As a result of this attack and related activities, tensions between North and South reached a boiling point.

A year later, the American South seceded. Suspected of being involved in the plotting of the attack, which was not true as he was against violence and even tried to dissuade Brown from attacking, Douglass “retreated” again for a while to the other side of the ocean. When he returned, the country was on the brink of civil war.

Lincoln and Douglass – a historic friendship

At the same time, the race for the presidency was underway and Abraham Lincoln was nominated as the Republican Party’s candidate. His election came as a surprise to many, as he was still relatively unknown and the loser of the recent battle for the Senate seat of his native Illinois. He had joined the young Republican Party in 1858, barely a few years old, founded to fight for the abolition of slavery. When he ran for the Senate nomination, his historic Divided House speech instantly made him the new leader of the anti-slavery movement: “I believe that this country cannot continue to exist as half free, half slave. It will become one or the other.”

The moment of decision has come, will the US stay together as a slave-owning society or a free society? Douglass, who had been spreading this message for years, agreed: “The law of the land can only be either freedom or slavery … The South must give up slavery or the North freedom, for they are as different as light and darkness, as heaven and hell.”

But history sometimes quickly forgets that the famous Lincoln, the great abolitionist and victor of the Civil War, was not always a staunch advocate of black human rights and an abolitionist. Although he was always ideologically opposed to slavery, he was also, especially at the beginning of his political career, strongly influenced by the state of mind and society and harboured typical prejudices against black people. He was convinced that the white and black races were too different to coexist peacefully and successfully, and he supported the so-called principle of colonisation, the idea of returning all blacks to Africa or even settling them elsewhere, say in South America. Lincoln knew little about slavery before he came to Washington – there were no slaves in Illinois, where he was from, and few blacks.

The Douglass vote reached Lincoln several times, and the two men eventually forged one of the most influential relationships in US political history. Lincoln, too, was a self-made and self-taught man who rose from poverty with courage and intelligence. He learned the law and slowly but steadily worked his way up the social ladder with his proverbial industry and diligence. He became increasingly convinced that slavery was wrong and, if he had initially believed that it would “breathe its natural death”, the events of the 1950s, when it not only persisted but even spread, made him increasingly active in political opposition.

But Douglass was initially sceptical about his presidential nomination, so he backed the Radical Abolitionist candidate, his friend Gerrit Smith. Lincoln was a pragmatist who recognised the importance of slavery to the Southern states, and because he wanted to keep the country together at all costs, he advocated only the gradual abolition of slavery before secession. Douglass resented this, but even a pragmatist himself, he was quick to support him when he won, convincing his supporters that “this is the best we have at the moment, and we must stick to it, for it is the only thing that will help us”.

Frederick immediately used his fame and influence to put pressure on the new administration to emancipate the slaves. “Worse than the war itself is the cause of it,” he said. Douglass also got blacks to join the Northern army and recruited them assiduously himself. He personally demanded equal pay for black soldiers from Lincoln. Lincoln, however, was by then a convinced abolitionist, and so in 1863 the Emancipation Proclamation freed all slaves in Confederate territory. Many historians believe that it was Frederick Douglass, whom Lincoln respected more than anyone, who helped him most in his personal growth from a moderate opponent of slavery to a convinced abolitionist and supporter of equality.

The abolition of slavery was written into the US Constitution by the 13th Amendment at the end of 1865, more than half a year after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Frederick Douglass was deeply affected by his death, and in memory of their friendship and in gratitude for the recruitment of black soldiers who contributed greatly to the victory of the North, Lincoln’s widow gave him her husband’s favourite walking stick.

Inequality after freedom

But as we know, the abolition of slavery did not bring equality to black people. Douglass was also cautious: “Our work does not end with the abolition of slavery, but only begins.” In the years after the Civil War, the so-called Reconstruction period did give more rights, such as the vote, but then the country soon sank back into backwardness and racial intolerance took over. At the end of the 19th century, racial segregation, especially in the South, was the basis of social relations which, through the Jim Crow laws, successfully perpetuated the division of people into whites and blacks, the privileged and the discriminated, the superior and the inferior. The doctrine of ‘equal but separate’ meant segregation in public places, schools, transport, access to services, real estate and jobs. This was compounded by physical violence and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Segregation laws were only abolished in 1965.

Frederick Douglass remained socially and politically active for the rest of his life, even taking on important government posts such as the diplomatic post in the Dominican Republic and the ambassadorship to Haiti.

His greatest contribution to humanity, however, was undoubtedly his awareness-raising and struggle against the institution of slavery, which he tirelessly led as a distinguished and unrivalled orator, activist and intellectual. Frederick Douglass was one of those individuals who contributed most to the abolition of the tragedy of slavery.