“The only misfortune is that we come from the workshop of a famous master, a kind of Stradivarius suis generis, who is no longer here to fix us. Unskilful hands do not know how to coax new sounds out of us, and we are pushing to the bottom of ourselves what no one knows how to bring out from there, because we have no lutenist”, wrote the then 38-year-old Frédéric Chopin to his childhood friend, the Polish composer Julian Fontana, 14 months before his death on 17 October 1848. He never found a soul mate to match his own, not even in the famous writer George Sand, with whom he shared his life for almost nine years. With loving relatives, devoted friends and a throng of admirers, he was alone. He opened his heart only in music, but even when composing, he was careful not to let his feelings be known to all. He did not like melodrama. Even when his sounds emerged from the depths of emotional storms, his music was pure and without exaggeration, but always original and perfect.

He was lucky. The child prodigy who loved black and white keys had only two teachers in his life. Neither of them tried to break the will of his genius, which they had recognised in him at an early age.

“The boy is taking an unusual path because his gifts are unusual,” another teacher, Joseph Elsner, persuaded Frédérick’s father, a French professor, that his son’s music would only be original if he played the way he felt, not the way the rules said he should. Chopin thus knew everything he needed to know by the age of 16: seven notes of the scale, which were enough to express his emotions.

From then on, he was only looking for his own style. Nothing else interested him, then or later, so his father allowed him to leave school at the age of 17 and two years later go to Vienna, where he was already considered a new rising star. The concert only cemented his status. “Under his supple hand, a velvet world of slight pain opened up, in which everyone groaned when they unexpectedly discovered a memory of their own numbness”, wrote Guy de Pourtalès, the author of one of his biographies.

“The noble delicacy of his touch, the indescribable dexterity of his technique, the perfect poise that reflects the deepest sensitivity, the clarity of his interpretation and his compositions, which bear the marks of a great genius, reveal a virtuoso, to whom nature has been particularly kind and who, without any previous publicity, appears on the horizon as one of its most dazzling meteors,” reported the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung after his second concert, in which he improvised as only Franz Liszt could have done alongside him. Only Chopin criticised his performance. He felt that he had played too softly, too quietly and not loud enough, but he concluded immediately afterwards that this was his way of playing and he preferred to be thought too soft rather than too loud.

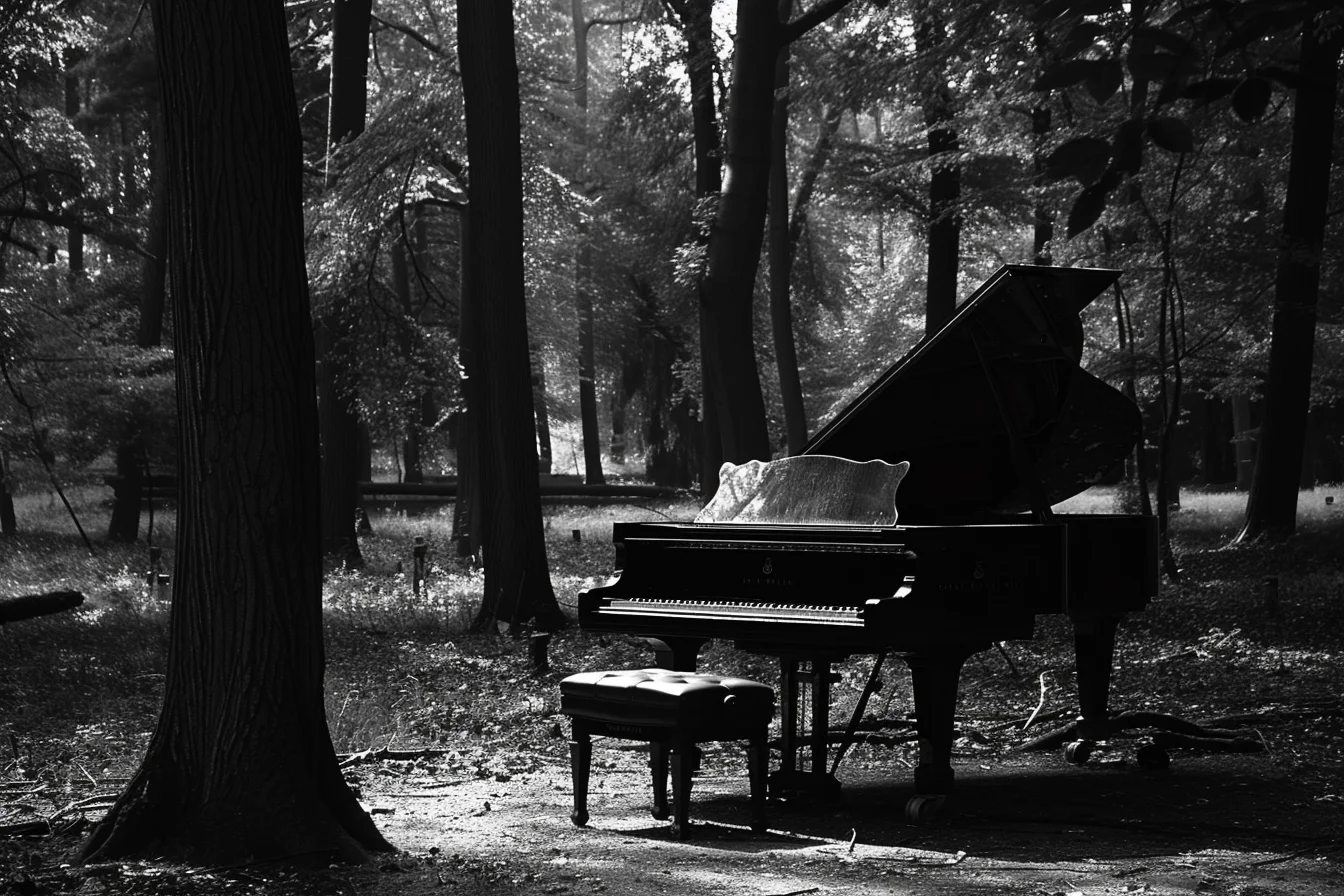

He returned home to Warsaw, where his family had moved from the nearby rural town of Żelazowa Wola eight months after his birth on 1 March 1810, prosperous but unhappy. He wrote to his friend Titus Wojciechowski that he had found ‘his ideal, perhaps in his misfortune’. He had fallen in love with the fair-haired Constance Gladkowska, whom he had seen singing in a minor role at the Warsaw Opera, and had now been dreaming of her “every night for six months”, “and I have never said a word to her”. She was the first, but by no means the last, woman to inspire his music. When he had no one to “reveal his heart” to, when he was “close” to her, he talked to the piano.

He composed Waltz No.3 Op.70 for Constanze, but it did not bring him relief. It is so “miserable to have no one with whom to share sorrow and joy”, he wrote to the absent Titus. What kept him going was his attachment to him and his love for Constance. “My work is driving me crazy. I write by necessity. I work day and night. I live in dreams and sleep when I am awake. Actually, it’s worse than that. I feel like I have to sleep all the time because I feel the same thing all the time. Instead of drawing strength from this drowsiness, I torture myself even more and keep sleeping.”

The Inner Man is a mute

It was clear that he had to go, but it was hard to leave his mother, to whom he was very attached, his sisters and his friends. He had many of them, because he could be a real burka, but behind the mask of pretentiousness and politeness he was always alone among people. “I imagine I am going to my death,” he explained to Titus why he was postponing his departure. He feared that he would never set foot on home soil again and that where he was going he would have nothing but music. On the first of December 1830, he left.

For political reasons, he never really saw Poland again, and neither did he see Constance. Two years after his departure, she married and later went blind. It was said that whenever she sang Quante lagrime per te versai …, which was so dear to Chopin, her eyes filled with tears.

He appeared in Vienna just as the revolt broke out in Poland. He wanted to return, but was stopped by his father’s words to persevere on the path for which he had sacrificed so much. But it was not easy. As a Pole, even his artistic friends at first shunned him, and when he found company, “all the dinners, social evenings, concerts and dances” bored him. “I had had enough of them. I am not allowed to do what I want: I have to dress, arrange, change, wear a hat and play in the salons of a quiet man, and then go home and fiddle on the piano. I have no confidant, I have to be polite to all people”, he wrote to Titus at Christmas, and on the first of January that he was on the verge of a really sad year which “I may not live to see the end of”.

Even if it is tender, restless and lonely, of course it is. He composed extremely well, but Vienna could offer him nothing that touched him. He decided to leave again, only he did not know where to go. He chose London and had a stopover in Paris written in his passport. It became his final stop.

Paris was buzzing with life at that very moment. There are nowhere as many pianists as here, Chopin reported home, but Paris was also full of all kinds of artists. The writer Amantine-Lucile-Aurore Dudevant, six years Chopin’s senior, better known under the pseudonym George Sand, wrote at the time: ‘How sweet it is to live! How beautiful it is in spite of worries, husbands, boredom, debts, relatives, slanders, in spite of sharp pains and annoying annoyances! It is intoxicating to live! To love, to be loved! That is happiness! This is heaven!” A divorced mother of two and a spokeswoman for love that transcends the barriers and norms of social class, she was renowned in Paris as a bold and brilliant woman.

Chopin had no idea that George Sand existed, but he knew well about the famous pianist Friedrich Kalkbrenner. He was given a great opportunity to become his pupil, under the right conditions, of course: he would study with him for three years, he would change his playing technique, because it was bad now, and he would compose differently, because he was not good at it now. Chopin quickly saw the black abyss behind the glittering façade. He would not allow Kalkbrenner to make his own recording of it and destroy what was “bold but noble”, he decided. His father, as always, supported him. It was clear to him that Frédéric “spent little time on the technique of his playing”, but also that “connoisseurs can see genius at first sight, but not when it is just rising”.

Chopin’s former teacher Joseph Elsner made it clear that Kalkbrenner was just enraged by envy. He and other pianists have recognised in him a genius, and he fears that he will surpass him. In three years, he told Chopin, we could “stop what nature is developing of its own accord” and advised him to rely on his feelings. Let his genius guide him, let him remain as he is and let him keep his rhythm, the rhythm he brought from Poland and which he wove into his music in adapted forms until his death.

The decision was simple: Chopin thanked Kalkbrenner for the offer and gave a concert in February 1832. At the time, and every time thereafter, he found it excruciating to play in front of a crowd. He preferred to wander around the black and white keys for his own soul or for selected friends, especially Polish emigrants.

In the front row sat the piano virtuoso Franz Liszt, a year younger than him. When he heard the music in which “each one heard the cry of his innermost self”, he became his lifelong friend, even though in the years to come great efforts were made to make them, at one time the best-paid pianists in Paris, rivals and adversaries.

The praise came from all sides and Chopin accepted it without false modesty, but he would have preferred to have some money left over after his expenses were paid. He liked Paris, where there was something for everyone, but with almost no money and no friends, he headed for America. “I like being around people. I get to know them easily, so I’m tired of being alone with acquaintances. But there is no one, no one who can understand me. My heart is beating in syncopes all the time. It’s hard for me. I want a moment of peace, of solitude, to not be seen or said anything to all day long,” he complained to Titus. He never had peace because there was always someone knocking at his door, and he was always sick and sore, even if “outwardly happy”.

He might indeed have left Paris if he had not accidentally played in the select company of Baron Rothschild. The requests for lessons began to pour in and he began to earn well. He bought his choice clothes, white gloves and a convertible, went to expensive dinners and had his home tastefully decorated, including chandeliers and silverware. He knew exactly what kind of environment he wanted to live in. Among other things, there had to be flowers in a vase at all times of the year.

Now he was calm and when he was calm he was creative. In 1833 he published five mazurkas (a Polish dance in three-quarter time), a trio for piano and cello, three nocturnes, twelve great etudes dedicated to Franz Liszt and a concerto in E minor. He continued at the same pace the following year. Now his works were being played by the most famous pianists, although no one but him could colour them with their original colours. But the 24-year-old Frédéric was again restless. “Chopin is healthy and robust. He confuses all the women. Men are jealous of him. He has come into fashion. We will probably soon be wearing gloves á la Chopin. But he is nevertheless torn by homesickness,’ wrote Antoine Orlowski. He soothed him with friendships and treats.

He ended up in the bed of Delfina Potocka, a 25-year-old married Polish countess. At her instigation, not his. With her sensuality and voice, which he adored when he accompanied her on the piano, she awakened the man in him, even though he was too timid to take the first step from platonic to physical love. Unfortunately, her husband found out about the affair all too soon and deported his wife to Poland. Only one letter she wrote to him from there survives: “I will not torture you with a long letter, but I do not want to be without news of your health and your plans for the future for much longer. I am sad because I know you are alone and abandoned …” She moaned a little more about her current situation and added: “Actually, life is nothing but uncanny dissonance.”

Franz Liszt also longed for harmony, running after every wing that whirred by, while the reserved and gentle Chopin was closer to the words of the poet Jean Paul Richter: “No human being can tell another human being how much he loves him; he only feels that he loves. The inner man has no language of his own: he is mute.”

Famous child of a famous writer

Even in his most difficult moments, Chopin did not speak of his heartbreaks, but he made no secret of his happiness when he met his parents in 1835. By then he was already in love again. At the age of 25, his heart was captured by 19-year-old Maria Wodzinska, the younger sister of the brothers who had once stayed in the boarding house his father had opened in their home. Her family treated him like a son until they got engaged. The Countess of Wodzinska agreed to the status-unsuitable betrothal, but it had to remain secret until the Count could be slowly prepared for it.

Chopin put his pain back into music. The first farewell to Maria was a waltz of farewell. He was too shy to betray it, but not so shy that he did not pay tribute to her. Maria also inspired the Ballade in G minor, one of his most personal works. It was written when he realised from letters from her and her mother that she would never be his wife.

The break-up of the engagement was expected, but no less painful for that. Chopin never recovered, emotionally or physically, although he never spoke of it. He tied Mary’s letters and the flower she had given him on their first goodbye, which had dried, with a silk ribbon and wrote moia bieda, or my misfortune, on the wrapping. Wherever he went, the packet went with him. Others only found out about him when they found him after his death.

Meanwhile, George Sand, who published her first book at the age of 27, lived a turbulent life full of passion and disappointment. 34 years old, divorced and mother to Maurice and Solange, she was convinced that the years of passion were behind her and her life had calmed down after four famous lovers. Chopin had arrived.

She arranged for them to meet. Chopin found her irritating. “Is she even a woman? Actually, I doubt it,” he said, looking at her, who was independent and self-reliant at a time when it was the original sin for women to be so. At the age of 27, he was still getting over Mary, but when they crossed paths again a year later, he was ready to give in to his passions.

Paris quickly became a hotbed of gossip and they wished for a quieter place, one that would be more suitable for Chopin’s health. He had still not fully recovered from an outbreak of jaundice, which was fatal in his time. He and his two children went to Majorca, but left Paris separately. Just as he did not proclaim his pain, Chopin did not want to hang his happiness on a large bell. It didn’t last very long either.

He caught a cold at the first rain and was laid up for a few days after arriving in Malorca. Bronchitis was followed by a renewed outbreak of jaundice. From the Garden House, where they were staying, he wrote wittily to a friend: “Three of the most famous doctors on the island have gathered for a consultation. One of them sniffed what I spat out. The other knocked me where I spat from. The third listened while I spat. The first said I was going to perish. The second said I would perish. The third said I was already dead. And yet I live as I have lived in the past.” What bothered him most about his illness was that he was late with his work and his prelude, and that his piano had still not been sent for during his stay in Majorca.

But it could be distracted by anything else. The money is drying up. Food was being sold to them at extortionate prices. The house in the garden was too small and unheated. When word got out about his jealousy, nobody wanted to serve them. In the end, the owner threw them out of the house and demanded that they whitewash it at their own expense.

Chopin and Sandova and their children stayed in the much cheaper, more or less abandoned Waldemar Carthusian Carthusian. “This is poetry, this is solitude, this is everything that is the most exquisite under the sun!” she enthused. Chopin described his cell as coffin-like, with a dusty ceiling and small windows, a bed, a table and a massive candlestick, the only luxury: “You can shout very loudly without anyone hearing you; in a word, I am writing from a very strange place.” But he liked the moon, except that soon he could no longer admire it, because the new rains made him ill again.

Now everything was getting on his nerves. Only composing and playing calmed him when his piano finally arrived. Alone in the empty monastery, he was overwhelmed with horror, but then he wrote down the most beautiful parts of his compositions. Once, when George was returning home just as a storm was breaking, he was shocked to death, convinced that she had died. Out of this threatening anxiety, according to some, came Prelude No. 6, which expresses all the horror and amorous anguish he experienced. The thought of losing the woman who had brought him back to life broke his heart, Franz Liszt was convinced, but also that Chopin was just an interesting adventure for Sand.

In any case, after two months of torture, when, among other things, their clothes were mouldering on their bodies, they had had enough of Malorca. The passion that had driven them there was almost gone. For Chopin, life was over. He wanted to return to his work, the only thing he had left. Sandova looked forward to her former life and her friends: “Another month and both Chopin and I would have died in Spain; he of dullness and disgust, I of anger and frustration.”

Chopin was so weak that he could hardly make the journey to Marseille, but the doctors there brought him back to himself sufficiently to be able to play, walk and talk again, after being almost mute for several weeks due to the exertions. In May 1839, he crossed the threshold of the country chateau of Nohant, home of George Sand, for the first time. He took a liking to him, but did not renew their passion. George no longer saw Chopin as a man, but only as a helpless child whom she worried would be buried if she ever fell in love again, and she fell in love easily. How would she leave him? Now he was a guest in her house. Did she even want him to become a member of the family, even though neither of them had thought of marriage?

Chopin did not know about her doubts and did not share them. What he did not share was the quiet everyday life in Nohant, when they devoted themselves to their work and entertained her friends. In the evening he played, but only for her, and went to bed with the children, while Sandova began to prepare for the next day’s lesson, because she was teaching the children herself.

As summer began to turn to autumn, the tranquillity of Nohant no longer suited Chopin either. He was a child of the city. He missed teaching, which was the main source of his income. George also wanted to go to Paris, but he and Frédéric had no plans to live together, and only wrote letters to their friends asking them to find them apartments nearby.

Chopin’s demands were in line with his dandyish preferences. The wallpaper, for example, had to be dove-grey, shiny and smooth, but only in the rooms; in the hall it had to be different. He also allowed his friends to choose something more fashionable at the moment if they found it, but it had to be “simple, modest and elegant”. Above all, Sandova wanted a quiet neighbourhood.

When the friends found what they were looking for, they had to take care of Chopin’s appearance. He wanted a new hat, tailor-made and the latest fashion, and new trousers. The colour and material were his own, the tailor already had the measurements. The waistcoat had to be made of velvet with a very slight and barely visible pattern and of good quality material.

He got everything he wanted, but he didn’t last long in his apartment. After a year with George, he got used to her and her care, so he rented a flat in her house. He now lived a calm and consequently fruitful life, although his normal daily routine was so exhausting that he could only survive on a few drops of opium in a glass of water.

To the boys with a yearning for perfection

In the morning he taught. He often played to his pupils himself, and when he didn’t, he explained to them about simplicity as the last mark of art. He passed on to them his playing technique, which older pianists resented so much. They were trying to achieve the same sound with all their fingers, he wanted to give each finger a different role and sound. “The thing is to take advantage of these differences. That’s the whole art of fingering, in other words,” he explained.

He placed them on the keyboard so that they rested on e, fis, gis, ais and h, which he believed was the natural position of the hand. With practice, all his fingers became independent and he was able to strike notes that were very far apart, which was almost impossible for other pianists. His finger technique made his touch softer and his hand completely calm. He was in complete control of his fingers. He poured his feelings into each one and created his famous blue tone by touching each one.

He gave his disciples everything he knew, but none of them reached him. He could not, because, in the words of Franz Liszt, Chopin “appeared among us as a phantom and disappeared as a phantom”. He was inimitable.

And as such, every afternoon he worked with discipline on the ideas that usually came to him in the summer, most often while walking, thinking or at the piano. He played them for himself, sang them and changed them. In a letter, George reported to a friend how traumatic it had been for him to create. Sometimes, locked in his room, he would cry, go up and down, break pens, repeat and change one bar a hundred times, write it down and cross it out just as many times, and then start all over again the next day with meticulous and desperate persistence. For six weeks he could sit on a single page and finally write it down as he had written it at the beginning.

Sanda was a complete stranger to what he was doing. She worked hard and well, but she never aspired to perfection, so she could not understand Chopin’s longing for it.

She had dinner with him without any problems and hosted her friends, who slowly became his friends too. Eugène Delacroix, a painter 12 years his senior, was the closest to him, even though he had no relationship with painting and disliked his paintings. The two men were also quite different, but they were similar in temperament. Delacroix was described by the poet Charles Baudelaire, who was much younger than him, as a mixture of scepticism, politeness, conceit, ardent will, cunning, despotism, a special benevolence and a directed tenderness “which always accompanies genius”. Chopin was similar: he disliked crowds, was always politely sceptical and constantly hid his heart. Both were restless, thoughtful, reserved and, of course, ill. They liked to be in select company, but Delacroix took his maid to the Louvre and explained painting to her, while Chopin played to his servant.

One of the few things they agreed on was that Mozart was a god. According to Chopin, he had found “the principles of all liberties”, but he was not perfect. In his opera Don Juan, which was very dear to him, he found what he considered to be some bad passages. “He could forget what he rejected, but he could not come to terms with it at all,” Liszt explained. Chopin had a lot to say about Beethoven, but almost nothing to say about Bach, whom he admired completely.

Delacroix admired Chopin’s music. He found it modern, and it remains so today. Chopin was far ahead of his time. Everybody saw him as a genius and therefore expected him to write an opera. I am not learned enough for it, he dismissed them. He preferred to write waltzes, mazurkas, etudes, preludes, nocturnes and other “small” works which, when he breathed his soul into them and worked them out in detail, became “big” and perfect. And they probably weren’t small at all for him. He judged music by his own standards, not by the standards of those who expected “more” from him.

His peer and friend Franz Liszt was certainly not one of them. They were also quite different, both in character and playing technique, but they were friends. Liszt played Chopin’s compositions in his concerts, arguably the best of his contemporaries, but not as well as Chopin, whom the poet Heinrich Heine called Raphael at the piano, explaining that in his music ‘every note is a syllable, every beat a word’. Chopin poured his emotions into his music, but all the time he tried not to make them too obvious. Liszt was sure he recognised them. “He only needed art to play his own tragedy to himself”, he commented on the intertwining of his private life and his music.

But Chopin was not only serious. He sometimes played the laughing, twirling or flickering of fantastic, witty and mocking figures, but he was no fun when it came to politics. His convictions were “independent, firm and unwavering”, but he never got involved in public fights, as Liszt and Berlioz did, for example, and he did not want to become the leader of any party.

In fact, music was the only thing that interested him. In October 1839, when he played for King Louis-Philippe at the age of 29, he was given a new patron. For the next three years he worked again, calmly, large and perfectly. Next to Liszt, he was the most sought-after pianist in Paris, and the hall where he performed in the spring of 1841 was packed. Liszt wrote an account of the concert for the Gazette musicale at his own request:

“Chopin rarely appeared in public, at very long intervals, but this very circumstance, which would surely have made any other artist forgotten and unknown, gave him a name independent of the vagaries of fashion, spared him from rivals, jealousy and injustice. Chopin has remained outside the immeasurable movement which for some years now has been driving artist-performers from all parts of the world into each other and against each other. He has always around him loyal followers, enthusiastic pupils and affectionate friends, who protect him from unpleasant struggles and tormenting insults, while at the same time constantly spreading his works and with them admiration for his genius and respect for his name.”

Chopin was just happy that the concert was over and he could go to Nohant, although he had never really liked nature or his friends George Sand there. In the summer they had a row about his pupil, Madame de Rozières. She had a little intrigue, according to Chopin, George defended her and Chopin was terrified of losing her.

He was indeed overtired those days, but his perceptions were correct. There was a restlessness in George, and when he sensed it, he liked to torture her mentally, and then he politely and coolly locked himself in his room. She spent her nights writing. She started work after midnight and went to bed towards tomorrow. Consciously or not, in Lucrezia Florian was describing their relationship. Every day she had him read what she had written. He would expressionlessly overlook the similarities, if he noticed them, and praise her work. He kept his feelings for her silent and put them to music. He no longer allowed her to himself, although he still loved her. She was only as one of his children, and she never understood him as such.

When they moved to Paris in the autumn of 1842, they again had separate apartments. When George spent part of the winter in Nohant, he was in Paris. He sent her reassuring letters telling her not to worry about him, as if his mood had begun to wander after he realised that their love was fading. Now they were bound only by their mutual concern, which, though sincere, no longer pierced their hearts. In 1846, that bond was broken. Not because of them, but because of Solange and Maurice.

Brother and sister had long been estranged, and Maurice also disliked Chopin. For his mother, he wanted something other than a relationship with a man everyone said was a genius, but he found him merely exhausting. On top of that, people were still looking at them sideways. He felt even less right to be criticised by Chopin, and rightly so.

In the end, it was Augusta, George Sand’s niece, who made it happen. She moved in with them and endeared herself to everyone except Solange and Chopin. The jealous Solange accused her of being Maurice’s lover, Chopin took her side, George her son’s, and the drama began. Storms rose and fell in Nohant, but Chopin kept on working. He wrote three new mazurkas, in B flat major, F minor and C sharp minor, Op. 63 and 65.

End of relationship, end of creativity

They were all unhappy, no one admitted it. As long as they could, they pretended that the break between George and Chopin was not final. The straw broke the camel’s back after a fierce argument in which Maurice and Chopin hurled all sorts of insults at each other, made up and soon jumped into each other’s hair again. Maurice threatened to leave home. George stopped him and now Chopin announced his departure. No one tried to stop him. On the first day of November 1846, or seven and a half years after he arrived in Nohant, sick and pale, he got into a carriage and drove off wrapped in a bedspread.

Now Chopin and Sand only knew about each other from other people, but George did everything she could to keep from him the details of an improper marriage forced by her daughter in 1847. She did not want him in their intimate family life and he knew that this was the end of their friendship. George wrote in her diary: ‘So I have reached 45 years of iron health and sometimes moodiness, but this lasts only a few darting hours, which I forget the next day …’. My soul feels good today and so does my body.” After that, she wrote again about how she was sick with worry about Chopin, but from then on her letters were full of contradictions, as if she wanted to apologise to herself and to the public for having excluded Chopin from her life.

He remained silent, as always. He was also silent when Solange’s marriage turned out to be a disaster, as he had predicted it would, and George was all distraught at the loss of her daughter. She had hoped that he would come to Nohant. He didn’t. Now even his friend was gone. George left him alone, but she quickly played the victim. She sent shocking letters around about how badly she felt for him and he, who was now her “enemy”, was sure to “tear her apart” with his reputation and friends.

After almost nine years together, she didn’t understand him any better than she did at the beginning, and she didn’t know him any better. Chopin had always felt an aversion to melodrama. He said nothing and reproached her for nothing. In a letter to his family, he mentioned only that George ‘wanted to get rid of my daughter and me at the same time because we were a nuisance’ and went on to say that he was not sorry that he had ‘helped her through eight of the most delicate years of her life, when her daughter was growing up and she was bringing up her son’. I am not sorry for all that I have suffered, but I am sorry that she broke her daughter, this plant that she had cared for so wonderfully and protected from so many storms, in her mother’s arms with a foolishness and a recklessness that could be forgiven in a twenty-year-old, but not in a forty-year-old.”

He predicted many more adventures for Sand, who had started writing her Memoirs at that time, but he was fading away. This time he could not even express his emotions through music. In February 1848, almost nine months after the break-up, he was still unable to work. He had lost music, his only source of consolation. He was still thinking about George. He reflected in a letter to his sister that he wanted to get lost in Nohant in any way he could. “God save her if she can’t tell true devotion from sycophancy. Otherwise, others may seem to be sycophants only to me, whereas her happiness is really where I cannot see it.”

For him, “this thing was over”, but their last meeting was still to come. On the fourth of March 1848, he was leaving a mutual friend just as George was arriving. She shook hands with him and he asked her for news of his daughter. She had not heard from her for a week, she replied. “Then I’ll tell you that you’re a grandmother. Solange has a baby girl and I am very happy to be the first to tell you the news,” he said with satisfaction. He saluted and was about to descend the stairs when his conscience overcame him. He could not go upstairs again because of his health, but he asked his friend to tell her that Solange and the little girl were well. George immediately came to him. She wanted to talk. How is he doing? Fine. And he was gone.

“There was no affection between us,” George wrote in The History of My Life, and Chopin wrote in a letter to a friend about the same incident that George “looked well. I am sure she is happy because of the triumph of the republican idea”. Eight days earlier, the revolution had broken out.

Chopin no longer had the will to do anything. He also stopped fighting the yeti, but was persuaded to give a concert on 16 February 1848. Afterwards, he almost fainted from the exertion, and his listeners from his music. “The unearthly genius was a man of the word. And with what success, with what fire!”, the Gazetti musicale enthused about the concert, which turned out to be Chopin’s last.

He just wanted to leave. At the invitation of his pupil Mrs Sterling, he set off for England with his three pianos. The change was pleasant at first, but the good feeling did not last long. He was tormented by bad news about the political situation in Poland and Solange’s disintegrating marriage, which made him think of George again. He stayed out late every night. In the morning he taught classes to earn money for his expensive flat, carriage and servants, but he did not want to perform because he did not rehearse. He started spitting blood again.

After appearing in three private concerts, he was a success, but in his letters he reported that he was “suffering from a foolish homesickness and although I am completely resigned to my fate, I am worried for God knows what reason about what is going to happen to me”. At the age of 38, he explained: “I don’t really feel anything anymore. I’m just living and waiting patiently for the end”.

Scotland was noticeably better. He got everything he wanted before he wanted it, he had peace and all the entertainment they could offer him, but everywhere he went he was dying of coughing and boredom. On top of that, he did not like the English. “They weigh everything in sterling. They only like art because it’s a luxury. They are a great people, but so special that I can understand why a man can get stiff here: you turn into a machine.” His performances were accused of being breathless, but he was so ill that they had to carry him up the stairs. He felt completely alone. “I’m getting weaker all the time. I can’t compose any more. I don’t lack desire, more physical strength.”

He longed for France and Nohant, where the bad news was coming from. George had to flee Paris to Tours because she was no longer welcome in Nohant. Chopin felt sorry for her, but was convinced that she had brought it on herself.

On his return from Scotland, he promptly collapsed in London. He wanted to go to Paris, but at the same time he wondered what he was going back to. He wrote his will, strengthened himself a little and made a few more appearances, then in October 1848 he welcomed back his apartment on the Place d’Orléans. He was cheered up, and so were his friends, and the doctors tried to get him back on his feet. He did not know that he had no money for them. He had never had control over it, and now he couldn’t even earn it because he couldn’t teach. His friends secretly lent him money.

On the verge of death, he wished to see his mother and sister Ludovika one last time. He was not allowed to go to Poland because of the political situation, so they came to him. They found him without a voice, communicating only with signs. It had been like this for six weeks. He was surrounded by friends and relatives. George Sand was not called, but a telegram was sent to Delfina Potocki, his lover, when he was 25. She said, “This is why God is delaying so much and not calling me to Himself, He wanted to leave me the joy of her coming to visit me.” He wanted her to sing to him. Twice. She hadn’t finished when he started to croak.

He spent the night. The next morning, on 16 October, he lost his voice again and lost consciousness for a few hours. When he regained consciousness, he wrote: “When this earth suffocates me, I beg you to open my body so that I may not be buried alive.” He wanted all his musical drafts burned because “I do not want works unworthy of an audience to be spread under the responsibility of my name”. During the night his condition worsened. The doctor asked him if he was unwell. “No more,” he replied. At two o’clock on the morning of 17 October 1849, he was gone.

Thirteen days later, his body was lowered into the grave at Père-Lachaise Cemetery, in the presence of everyone who mattered in Paris and around. There was no heart in it. His sister smuggled it to Warsaw, where it is still preserved in the Church of the Holy Cross. A few years ago, scientists wanted to open the glass container in which it lay to make sure for sure that he had indeed died of jaundice. They were not allowed. Chopin’s heart is the heart of Poland. He always carried it with him and wove its rhythms, which accompanied him through his youth, into his music, modified by the passage of time.