In July 1936, the heat in Key West was unbearable. The yacht Pilar had docked after six weeks of fishing around the Bimini, and its captain, Ernest Hemingway, tanned and unshaven, in dirty fishing trousers and a torn shirt, was slowly marching towards the big house he shared with his second wife, Pauline, and their two sons, Patrick and Gregory. The trip to Bimini was a success, he caught a huge tuna right from the start and, after seven hours of struggle, hauled it on board. Just as successful as the fishing trip was his meeting with the editor of Esquire magazine, who suggested that he put together a book of short stories about the Caribbean rum-runner Henry Morgan, which would take him to the top of the literary world, where he believed he belonged.

In his early twenties, when he was still living in a small apartment in Paris with his first wife Hadley and had managed to publish a few short stories, he was one of the most admired writers of the lost post-war generation. Yet it would be hard to say that he made good use of his success. It was not until his second wife, Pauline, a sharp and caustic woman, the daughter of one of the richest landowners in Kansas, that money came into his life. Their uncle was happy to buy them a house, and he paid for their safaris in Africa, including guides and private planes. With Pauline’s arrival in his life, gone were the days when he would squeeze into Parisian cafés to have a quiet place to write, buy the cheapest train tickets to go to the horse races in Auteuil and carry sandwiches wrapped in paper.

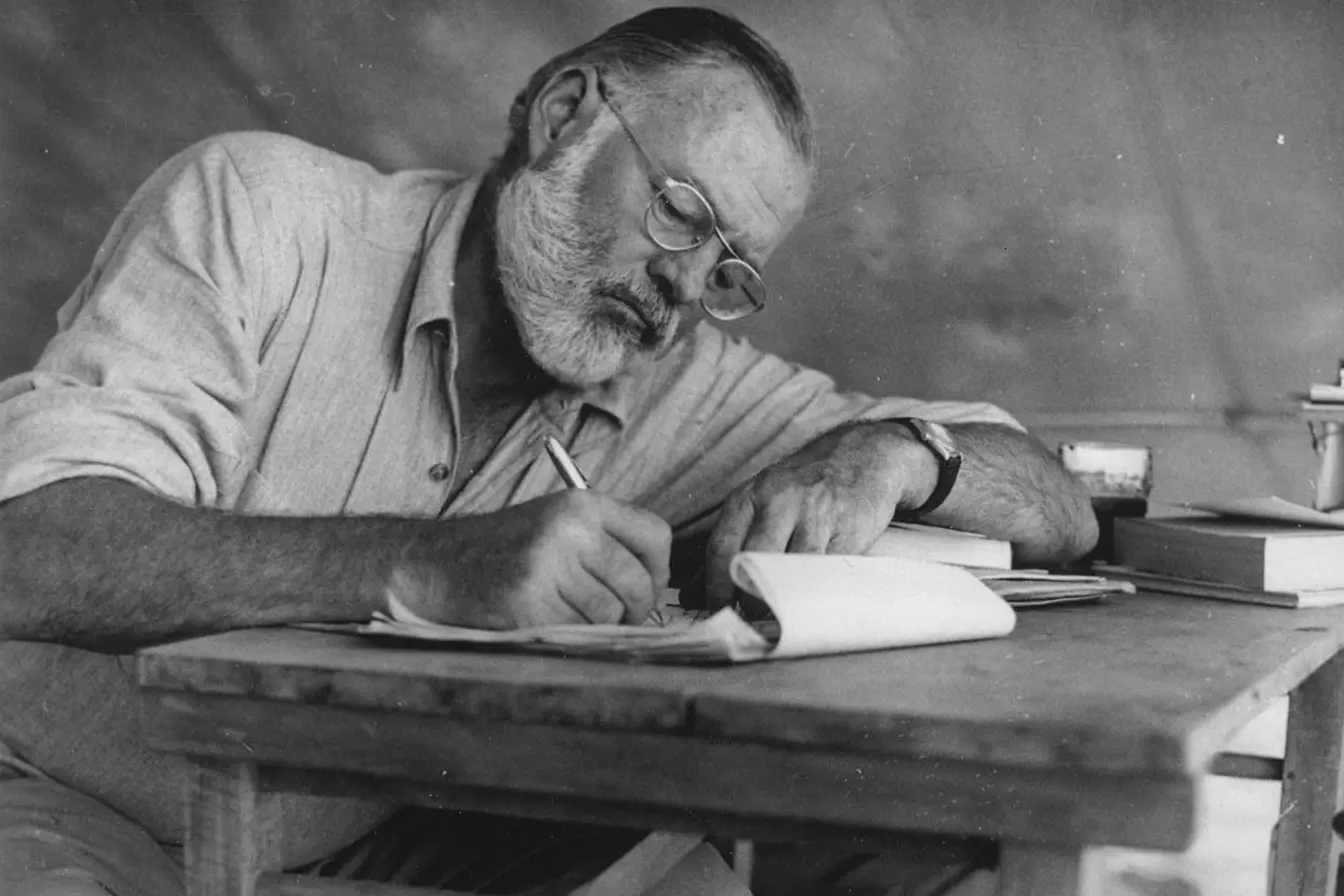

Despite all this, something went wrong in the years after the publication of Goodbye to Arms. Old friends with whom he used to talk about art and life over a whisky were replaced by sportsmen with whom he hunted game, fishermen with whom he went big-fish hunting, and rich men who visited his wife. He was worried that his success had dulled his power as a writer, that he had in fact sold his talent.

All the books he wrote during this period, even The Green Hills of Africa, were received with mixed feelings and sold poorly. But Gingrich, the publisher, put pressure on him. “Write something good already”, he urged him. But what should he write? After all the years of economic depression and the growth of fascism in Europe, his tales of a lost generation living abroad, bullfighting, hunting African game and fishing in the Caribbean seemed exotic, if not trivial.

Readers were interested in engaged authors such as John Steinbeck and John Dos Passos. What if you wrote something about Spain and went there, because that was where the exciting news was coming from? But he had already loved Spain when he was first there. He quickly dismissed the thought. Pauline was already preparing their Ford for a trip to Wyoming, where he would be able to hunt, fish, shoot deer, listen to the wind rustle the pines, watch the Yellowstone River from under the cabin, and write the novella that would revive his fame.

Then he got his hands on Time magazine, whose front page was dedicated to his former friend Dos Passos. They had been friends for years and travelled together, but when Dos Passos set out to write his trilogy about America’s watershed times and social moments, it hurt Hemingway’s self-love.

Hemingway included him in a novella he wrote in Wyoming, already 30,000 words long, in the person of an impotent, radical writer living on loans from his rich friends. Now he was staring at a photograph of Dos Passos in Time and reading an article that called the Passos trilogy the most audacious writing project of the century and compared it to the novel War and Peace.

He took a pen and wrote to his editor that he was working hard and would finish the novella, and then he would go to Spain, hoping that the shooting would not stop there. Later, in Key West, he struggled to connect the dots between the events of the novella he was writing. The main character, Harry Morgan, would of course die in the end after being wounded during a failed bank robbery, and another important figure in the novel, the millionaire Tommy Bradley, would support the Cuban revolutionaries and bring a load of dynamite to Cuba to blow up a bridge. Hemingway thought it best to go to Cuba and check the geographical data.

Meanwhile, Dos Passos was celebrating the success of the last book of his trilogy. Sales did not go well, but the reviews were excellent. He then met Joris Ivens, a Dutch documentary filmmaker. He had recently returned from Moscow, where he had lived for two years, drinking vodka and socialising with real people; the Hungarian revolutionary Bela Kun and the directors Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Meyerhold. Although he was employed by a Soviet film company, he did not get a job, because all film projects were given only to reliable Party people. In a climate of increasing Stalinist pressure, he even managed to get permission to go on a “creative” holiday to America.

He now circulated between Hollywood and the advanced intelligence circles of Greenwich Village. He was convinced that Dos Passos would be deeply disturbed by his idea of making a documentary about the causes of the Spanish Civil War, which was to appear in cinemas in 1937. They needed sponsorship money and a few neutral-sounding names to work on the film. Someone was to write the script and Ivens immediately thought of Hemingway.

A man in a T-shirt and dirty trousers

In July 1936, Martha Gellhorn accepted a lunch invitation in London from Herbert George Wells, the British author of the famous novels The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds. She was a young freelance journalist who also wanted to become a writer. Europe was a magnet for her, and she sent articles from there to America, trying unsuccessfully to find work at Time magazine and the New Yorker before she could get there.

Now it was in Europe, which was undergoing profound changes at that very moment. Germany was becoming more and more belligerent, Europe was still in depression, the Popular Front had come to power in France and introduced some classic democratic rights. Germany had failed her terribly. Inscriptions such as Juden verboten were a real slap in the face to her, because her parents were half-Jewish. “I’ve had enough of Europe,” she wrote to a friend, and returned to America, to her hometown of St. Louis, and spent the whole winter keeping her widowed mother company.

She was delighted that the newspapers published some of her articles from Europe. She also described her impressions of the trip to the American First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, as her mother was a personal friend of the First Lady. It was Martha’s mother who first spotted the Sloppy Joe’s Bar sign in Key West. They had always spent Christmas together in St. Louis, but after her husband’s death, Martha’s mother wanted to spend the holidays differently for the first time, and they decided on sleepy Key West in the far south of Florida. Martha’s brother joined them on the trip.

The café was dark, cold and full of grit. A man in a worn T-shirt and dirty shorts, tied around his waist with a rope, sat in the corner reading the mail. When the three of them entered, he looked at them. At first he thought that Martha and her brother were a couple, and thought to himself that he only needed three days, and he would distract Martha from the “young snot”. But this time he didn’t need them at all, because the shy girl spread her arms and introduced herself to him. He was, after all, her writing idol, she had a picture of him hanging on the wall of her room and she had used words from his novels several times in her short stories. How lucky to bump into him in this very café.

After the presentation, Hemingway told them that he had spent some time in St. Louis in his youth and that he was ready to show them the most beautiful beaches in Key West. They ordered drinks, once, twice, and then a friend of Hemingway’s came by. He was sent by Pauline, Hemingway’s wife, who was in the house preparing a fish supper for friends and wondered why he wasn’t home yet. Hemingway told his friend to tell her he would join them later.

For the next two weeks, he showed the Gellhorns everything there was to see in Key West, and when her mother and brother went home, Martha stayed in the hotel for another two weeks. Hemingway took her swimming, they shopped in small stores, and spent most of the time talking about writing and literature, the situation in Europe and the war in Spain. They were a handsome couple, she in French Riviera dresses, he in dirty shorts and spaghetti straps.

“I suppose Ernest is helping Miss Gellhorn with her writing again,” Pauline said angrily. “When a young unmarried woman becomes a married man’s best friend, what usually happens in the end is that the man divorces and marries his best friend.”

This is how Hemingway later described the events of those days. Martha Gellhorn was beautiful, bright, educated, with connections in the White House, and a skilled journalist with a desire to become a writer. She was flattered by the attention of a well-known writer and could not help boasting about it in her letters to Eleanor Roosevelt. She also mentioned that the writer was not only an anti-fascist in words, but that he had paid for the transport of two Americans who had joined the International Brigades in Spain.

When she finally left Key West, Hemingway took the opportunity to make a business trip to New York to meet Dos Passos and Joris Ivens, who had invited him to join their Spanish project. In addition, the North American Newspaper Association (NANA) wanted him to travel to Spain and report on the civil war from there. He might be able to find a suitable journalistic job for Martha in Spain. In Miami they entered a dormitory together and even when Martha had to change trains for St. Louis, they kept in touch, by phone and in writing.

Hemingway had a lot of work to do in New York. First, he told his publisher that he had not yet finished the novel he was writing in Wyoming. He signed a contract for stories about the Spanish War. Most of his time in New York was spent negotiating his participation in the Dos Passos and Ivens documentaries.

Ivens has since travelled to Spain and Hemingway is expected to join him soon. Ivens had already obtained all possible permissions to film from the socialist government, the communists and the anarchists, and so he arrived in Valencia on 22 January 1937 with his cameraman, 200 kilos of luggage and three cameras. He immediately went on to Madrid, found an old acquaintance from Moscow, Mikhail Koltsov, listened to the stories of Enrique Líster, the commander of the 11th Division, and Dolores Ibárruri.

Over the next few days, he photographed everyday events; townspeople rebuilding destroyed homes, soldiers shaving at the barber’s, people running scared when the bombs started falling. Then rumours spread that the Nationalists had launched an offensive to seize the main road linking Madrid with Valencia. Good footage of the actual fighting could have been taken here, but heavy rain prevented filming.

They had better luck with the cameraman during the attack by the nationalists on the railway bridge crossing the Jarama. They rode their motorbikes from one position to another and filmed on the spot. They returned to Madrid and attended a farewell party for the Russian engineer Gorkin. Champagne flowed in streams, toasts were made, Russian and Spanish songs were sung. The next morning Koltsev said to him: ‘We are going to arrest Gorkin in Odessa. The matter is, of course, political. Are you surprised about the farewell party? That is why we gave it to him. The French also gave the condemned man rum before they took him to the guillotine. These days, we just give people champagne.”

Dos Passos, Hemingway and all the other people who are to work on a documentary about Spain meet at Club 21 in New York. Joris Ivens had been there before, Dos Passos had known it since 1916 and had written extensively on its literature, but Hemingway’s knowledge of the country was limited mainly to watching bullfights and drinking sangria. What he himself called the tragedy of the corrida was for him only a substitute for the tragedy of war. It was therefore important to him that the documentary should be about war and death and be full of scenes of battle and devastation.

At the end of the meeting, Martha Gellhorn showed up in a modern orange dress and Hemingway told everyone that she would also be going to Spain as a correspondent for Collier’s magazine. Dos Passos, who was a great friend of Pauline’s, knew what was going on, but kept politely silent.

Towards the end of February, Hemingway boarded a ship bound for Le Havre. Before leaving, he told reporters at a press conference that he was going to report on “a new kind of war in which everybody is involved, including civilians, and if there are fascist bombs falling, he’ll take a bottle of whisky and have a drink”.

Hotel Florida

The weather in Paris was bad and the late snow was sticking to my clothes. The Popular Front government of Prime Minister Leon Blum, despite its empty coffers, had predicted that the reforms would hold, but the people were in a bad mood and depressed. The left was outraged by André Gide’s book, Return from the USSR, in which he described how food in Russia was poor and even scarce, that almost nothing could be bought, that people were only interested in survival, and that Stalin’s cult of personality had taken on almost unbelievable proportions.

Hemingway, arriving from Le Havre, was in his room at Montparnasse collecting news about Spain. An acquaintance who had come from there advised him to take as much tinned food, warm clothes and money as possible. The Nationalist offensive, backed by 35 000 Italian soldiers, was at least for the time being stopped by the Republicans at Guadalajara.

Then the weather cleared and the Republican aircraft and Russian-made T-26 tanks drove the Italians into flight. Madrid celebrated the first great victory of the Civil War. But the Battle of Guadalajara was coming to an end, and Hemingway could only report on its last phase. He titled his article “The greatest Italian defeat since Kobarid”.

Dos Passos only travelled to Spain in mid-March, ignoring his Spanish friend’s warning to be careful who he meets and talks to. “If the communists in Spain don’t like someone, they shoot them immediately,” he explained. But he was sure that nothing like that could happen to him. He was more worried about Hemingway, whom he knew could not always keep his mouth shut. “I hope I see him alive,” he sighed.

In March 1937, Martha Gellhorn also crossed the border at Puigcerda in Catalonia, showed her papers to customs and changed trains for Barcelona, which was full of recruits bound for the front. They were singing and joking and death seemed still unknowably far away. She was cold, tired and hungry. She travelled from Barcelona to Madrid by car, in the company of a young journalist, Ted Allen. She made the impression on him that mature and attractive women make on inexperienced young men. He tried to please her, while she watched intently out of the car window to see what was going on. There were more and more military vehicles on the road, guards were constantly stopping them and checking their documents.

As they approached Madrid, they heard a distant drumming. “It’s the cannons,” said Allen, but Martha remained silent. At the Florida Hotel, the receptionist explained that Hemingway was not at the hotel. That evening, she sat alone in her room until Ted Allen came to visit her. He sat on the edge of the bed and, as was his custom, talked to her. He was just explaining something to her frantically when there was a slight knock and a moment later a large man with a moustache and glasses entered. Allen recognised Hemingway immediately and said goodbye quickly.

In the morning, Martha was woken up by a drumming. The Nationalists were bombing the city. She wanted to find Hemingway, but the hotel room door was locked. In fear and rage, she started banging on it, banging until a hotel clerk came and opened it for her. So they locked her in, but what were they thinking, she raged, and went down the corridor in the direction from where the men’s voices were coming. She opened the door and found Hemingway playing poker with the International Brigades.

Of course he regretted that she was frightened, but he explained that he had locked her in the room so that no one would disturb her at night. She turned on her heel in offence and went back to her room. In the morning, she was just brushing her teeth when she heard the screeching howl of a grenade, which moments later fell in front of the hotel entrance and decapitated her husband, who was standing on the pavement. Ivens, who had also checked into the hotel in the meantime, rushed with a cameraman to film the body.

After breakfast, Hemingway and he went to the Ministry of Propaganda and both got a pass to visit the front at Yarama, where both sides dug into trenches, shelled each other unsuccessfully, and from time to time tried to turn the situation on the battlefield to their advantage by ambushes. As they were not directly on the front line, it was still quite calm and they were able to enjoy a picnic by a nearby stream. Towards evening they went to Morata, where there was a military hospital, and when one of the patients, an American soldier from the International Brigades, Robert Raven, heard that Hemingway was there, he wanted to greet him. He was blind because the grenade had exploded just a few metres from him.

Hemingway almost dared not look at his ruined face, which looked as if he had been pushed into the mud and then baked in the sun. “Listen, dude,” Hemingway comforted him, “it’s going to be all right. You’ll still be able to talk on the radio.” Raven tried to smile, “Maybe, because you’ll come and see me again?” And Hemingway lied, “Sure, it’s a deal.”

Although Martha was convinced before her arrival that Madrid would be a great adventure for her, she was going through a difficult time. First there was the constant noise of the guns; the crack of the rifles and the machine guns, the explosions of the grenades and the loudspeakers in the Casa de Campo, which blasted out music to “shell” the enemy. At night, despite the heaters, she felt cold. She was hungry all the time, and when she did manage to get something to eat, she was horrified by the food. She despised the people she met. She found Koltz’s mistress sinister, the Russian writer Iliya Ehrenburg arrogant, Errol Flynn foolish, Hemingway’s acquaintance Jodie Herbst vulgar.

She wondered what kind of relationship they had. She came to Spain to be with him, but she hardly ever saw him. He came and went, always dressed as if he were a worker, with a black beret on his head and a torn sleeveless shirt, cavorting with the acquaintances he had made in the meantime, most of them from military circles.

There was the Pole known as General Walter, Colonel Juan Modesto tried to conquer it, the police chief Quintanilla was a cynic and there were those “terrible” Russians, from Koltsov to Ehrenburg. And, of course, there was Ivens, who took on the role of Hemingway’s tutor and was constantly explaining to him what the anti-fascist struggle actually meant. Of course, they all drank a lot, whisky being their favourite. She found all this terrible. “Life here is completely different from the life I knew before.”

Although Hemingway loved to talk about strategy and tactics in war with his friends, his only real military experience was in the First World War, when as a bare-bearded young man in Gorizia he drove a Red Cross wagon and distributed mail, chocolate and cigarettes to soldiers in the trenches. A grenade explosion wounded his knee and landed him in hospital. Although he had promised Pauline that he would stay out of harm’s way, he was desperate to see real fighting in Spain. However, most of the fight scenes for the documentary had already been filmed by Ivens, so he was eagerly awaiting his next opportunity.

And it soon showed. The Nationalists entrenched themselves in the Casa de Campo, from where they could fire with impunity into the very heart of Madrid from the heights of the Cerro Garabitas, protecting their soldiers who were still in the university town. The Republicans therefore hoped to drive the enemy from their positions by a surprise attack on 14 April. Hemingway and Ivens were given permission to film, but not directly from the front line.

It was a warm spring day when the cameras were taken to the third floor of an abandoned house with a balcony. They protected them with old clothes they found in a closet and filmed all afternoon; tanks moving like bugs in the distance up and down the battlefield, soldiers like children’s lead toys running and crawling on the ground, getting up and running on again. Here was the closest Hemingway had come to fighting since he arrived in Spain.

When they returned to the city at dusk, they could not hide their disappointment. It was too far and “every fool could see that the offensive had been a failure”. Back at the hotel, Hemingway discovered that Martha had watched the battle as well as he had from the roof of a house near the hotel. But a Republican defeat was not something for which NANA was paying him $500 per article. Readers in New York, San Francisco, Chicago or St. Louis would never have believed that he was really close to the front line in a city where restaurants, theatres and shops are open. They wanted to smell the explosives and hear the gunshots. Never mind if someone dies in the process, never mind if a grenade explodes over your head, never mind if you have to run for cover and cower in mortal fear.

That is why he has accompanied his text with beautiful-sounding words about a very important battle, about the long-awaited attack, the bullets whizzing, the wounded screaming and the tanks burning. The article was neither about defeat nor about victory. He had the text proofread by Martha and then took it to Téléfonica, where there were censors who sometimes crossed things out and then sent it all to the NANE branch in London, which in turn passed it on to New York.

Robles has disappeared

A few days later, Dos Passos was hot on their heels, talking about nothing but the disappearance of his friend and translator José Robles Pazos. No one could tell him where he was. Margaro’s wife said only that people in plain clothes had come to see him, imprisoned him and accused him of conspiracy against the Republic. When she visited him in prison, he told her that it was all a mistake that would soon be cleared up, and then he disappeared and no one could tell where he was. Dos Passos wanted to continue his enquiries in Madrid, but Hemingway told him, “Drop this Robles thing. People disappear here every day. What if he has changed sides?” Dos Passos got upset. “Impossible. I’ve known him for years. He’s always on the right side.”

But making enquiries with the military authorities about missing persons has always been a very double-edged sword and could only harm the team making the documentary. Shortly after this event, he and Martha were invited to lunch by Luis Quintanilla, who some called “the executioner of Madrid” because he was the head of Madrid’s secret police. He lived in a luxurious apartment, the rooms of which were furnished with crystal chandeliers and the terrace had a beautiful view of the Casa de Campo. This was a different Madrid from the one they came from.

The disappeared José Robles was also discussed and Quintanilla was convinced that, whatever the outcome of the case, he would receive a fair trial. However, he felt that digging into the case could be detrimental to everyone. Martha and Hemingway shook their heads to figure out what to do.

While in Madrid, Hemingway sent a few telegrams and only one letter to his wife Paulina, but in none of them did he mention what everyone already knew – his relationship with Martha Gellhorn. Although he was not yet single, he proposed marriage to his young mistress. Martha did not answer him, but wrote in her diary, “I love him with all my heart.”

Fuentiduena de Tajo is 60 kilometres south-east of Madrid, close to the road to Valencia. The village, with its unpaved streets among poor houses with brick roofs, had a population of around 1 500 inhabitants at the time. Some of the houses were hit by Nationalist planes, and the inhabitants preferred to live in caves dug into the hillside by the river. But for Martha and Hemingway, who arrived there after the enemy planes had bombed Madrid, the village picture was reassuring.

Martha was in a bad mood this trip, as Dos Passos and his mistress joined them. He wanted to film some scenes of the social background of the civil war and Fuentiduena seemed ideal for this. Joris Ivens, on the other hand, had been arguing for some months that they should make two films about Spain. The first would be the war scenes that he had already shot and sent to New York, and the second would deal with village life.

Ivens discovered Fuentiduena while filming in the Jarama area. The village was poor and feudal, controlled for centuries by a handful of landlords. But when the war broke out, they were killed or fled, and the villagers collectivised their vineyards and pastures and built an irrigation plant with their own resources, drawing water from the nearby river. All this was excellent material for filming, and the socialist mayor of the village led Dos Passos to the irrigation plant. Men and children were fishing by the river. “These are anarchists,” he explained. “You will never see socialists lounging by the river while work in the fields is waiting. We’ve cleared out the fascists and the priests, now it’s the anarchists’ turn.”

Shortly before dawn on 22 April, two artillery shells hit the walls of the Florida Hotel. They were not aimed at the hotel, but at the nearby Téléfonice building, which housed government offices and telecommunications services. The air blast they caused targeted the walls and roof of the hotel and shook the windows. Doors opened on their own, plaster fell off and rats began to flee from the basement.

Dos Passos appeared in the corridor barefoot and wearing a bathrobe, Hemingway was fully dressed because he was going to Fuentiduena, and Martha was wearing a coat over her pyjamas. The other guests were also peeping out of their rooms in fright. Someone had brought coffee and toast and was offering it around. Meanwhile, the shelling continued, but no grenade hit the hotel.

At 7am, it was already dawn and the hotel staff started cleaning up the broken glass and plaster. This is war, and if there is war, these things happen, Hemingway thought, and decided to tell Dos Passos the real truth about the missing Robles. But that day was not the day, and the next day was not either, as everyone was attending the ceremony to celebrate the integration of the Martinez Barrio International Brigade into the regular Republican army.

Hemingway did not know that Quintanilla had in the meantime told Dos Passos that Robles was not facing a fair trial, in fact he was not facing any trial at all, because he had already been shot. He did not give a reason for this. “These are terrible times,” Quintanilla said apologetically. “To survive them, we have to be terrible too.” For decades afterwards, all sorts of stories circulated about Robles; that he was a pentathlete, that he had helped his brother escape from a Republican prison, that he had betrayed military secrets, and so on.

But it was probably only true that he knew too much about the Soviet plans for his Spanish protégés and knew important people who could have revealed them. Nevertheless, the news of Robles’s death threw Dos Passos off the rails. He imagined his last moments and described them to his friends: “They shove a cigarette in your hand, escort you into the courtyard and put you in front of six soldiers you’ve never seen before. They point it in your face, wait for the order and fire.”

When Hemingway also told him what he already knew, it came as a new shock. Not because of the news itself, but because of the questions that were coming to him. How did Hemingway know? Who told him, perhaps Russian advisers or Spanish officers? Could he have had his own fingers in the middle? It did not help that Hemingway suggested to him that Robles was probably a traitor and that he was getting what he deserved. “What are you going to write about Robles when you come back to America?” asked Hemingway. “The truth. But the question I have is, why are we fighting for human rights if we are then destroying them in the process?”

Dos Passos later wrote that he had “admired the simple Spanish people with all my heart”, but now he was increasingly convinced that their cause had been hijacked by the hard-liners, influenced by Moscow, and that the Party had nested in the very essence of the revolution. He travelled and Joris Ivens reported to Hemingway from Valencia that Dos Passos was still pursuing the same cause and was difficult to contain. So he suggested that he, not Dos Passos, should write the text for the voice-over narration for a documentary on Spain.

At the end of April 1937, when Martha left Spain, Hemingway met Quintanilla, the chief of the secret police in Madrid, in a hotel restaurant and sat down with him. The midday shelling had already begun and when the whistle of a grenade was heard, they both fell silent. Then Hemingway asked him how many people had died unjustly in Madrid. Quintanilla replied that it was not many. “Revolution is always a reckless thing. We have made some mistakes. But to err is human.”

Hemingway did not give up: “And how many mistakes have you made?” Quintanilla poured himself a glass of wine, thought about it and said, “Nineteen. Overall, there were a few mistakes.” Hemingway looked at his watch, got up and said he had to go to work. “Nonsense, there’s no work if you get hit by a grenade,” remarked the chief of the secret police, instinctively bowing his head as the grenade whistled and then exploded as it fell into the next alley.

Hemingway planned to leave Spain in two weeks, but he did not want to miss the opportunity to visit the front line at Guadarrama, where the Republicans were holding back the Nationalists from fortified positions on the forest slopes. This was the first time he had really been on the front line, as he and another journalist had been given a special pass. They were put into an armoured vehicle and driven along a route that was under enemy fire.

The vehicle lurched and creaked on the bumpy road, bullets bouncing off the steel sheet. They reached the top of a rise, where soldiers were singing and playing guitars, machine guns roared in the distance. The company commander, whom everyone called El Guerrero, appeared. He had been a truck driver before the war, then he had joined the Republican militia. He had been on this hill all winter and had seen his company almost destroyed by enemy grenades on several occasions. But he persevered, as did his wife, who fought by his side until she became pregnant and he sent her back to Madrid.

The fighters were poorly dressed and all wore only spaghetti straps, but they were happy. When the enemy mistakenly started firing mortars at a nearby fallen house instead of them, they almost burst out laughing. But they knew that war is not a game, because they had already lost many friends. “You will see our flag flying in every village at Christmas!” they called out to them as they bade them goodbye.

That night, Hemingway wrote what he thought was his last report from Spain at the Florida Hotel. In it, he did not mention El Guerrero, his wife or the fighters, only his ride in the armoured car, his enthusiasm and the good discipline of the Republican fighters. Two days later, he held a farewell meeting and then left for Paris.

Spanish soil

While he was writing his last report, one of the most tragic chapters of the Spanish Civil War was taking place in Guernica, an old Basque centre near Bilbao. On 25 April, Nationalist Radio issued a warning: ‘Franco will strike with all his might, any resistance against him is pointless. Basques! Surrender and save your lives!”

The next day, at half past four in the afternoon – it was the day of the Guernica Fair – the Condor planes of the German Legion flew over the town, dropped their deadly cargo and took off. When the alarm had gone off and the people had come out of their hiding places, the planes reappeared in the sky. First the bombers dropped their bombs, then the Heinkel planes flew in and started firing their machine guns. At five-fifteen minutes, three squadrons of Junker bombers dropped a carpet of bombs over the city. This destructive technique was first used by German planes two weeks ago, when they attacked the Republican positions near Oviedo.

But now they have attacked innocent civilians in this way and caused a real massacre. Whole families died under the rubble of houses, mad cows and horses rampaged through the streets, wounded men with third-degree burns wandered among the burning ruins. Although a reporter from the London Time newspaper arrived at the scene of the massacre the next morning and reported the devastation as a witness, his newspaper refused to publish it on the grounds that it would “offend German sensibilities” and left the text to the New York Times. The Nationalists immediately replied that Guernica had been burned down by the Republicans themselves.

Hemingway came to Paris in the hope of meeting Martha before they left for America on their respective ships. They had to be careful, because Hemingway was a public figure and had a lot of interviews waiting for him. He arrived in America on 18 May 1937 and immediately went to Key West. He was disturbed by Pauline’s letter in which she told him, “I wish you would sleep in my bed, use my bathroom and drink my whisky.”

But he had other plans. There was a documentary about Spain. Ivens told him that he wanted him to come to New York as soon as the film was roughly edited, to start preparing the accompanying text. There was also Martha, who, when she arrived in New York, said to the press: “The Republicans will win because they are braver.” And she immediately went to her publisher to sign the contract for the book on Spain, which was to be published in the autumn. Finally, there was the Congress of American Writers, mostly more left-leaning intellectuals, which Hemingway was to address. He hated public speeches, but he was aware that this inaugural speech would attract press attention that no amount of money could buy.

On 4 June, 3,500 people crowded into Carnegie Hall and 1,000 stayed outside the doors. It was an event that liberal intellectuals almost had to attend, as the main theme was “the writer and fascism”, and excerpts from the documentary Spanish Soil were shown. They were screened without sound, and Ivens said in his opening remarks that these pictures were “made on the front where every honest author should be”.

Then a sweaty Hemingway came on stage, his glasses fogging up and nervously tugging at his tie as if it would strangle him. “It is very dangerous to write the truth about war, and although the truth is worth the risk, the writer must decide for himself. Of course, it is more comfortable to argue scientifically about particular points of doctrine.” By the time he had finished, the audience was upright and tapping their feet.

As soon as the Congress was over, Hemingway headed back to Florida. The novel he had been promising his publisher for so long was not going well. He deleted, added to and deleted again parts of it. He came up with the idea of including the abridged story in a collection of other stories, including Snow on Kilimanjaro and a few others, and ending the book with his speech at Carnegie Hall, which had so impressed those present, and giving it the title To Have and Not to Have. He decided to think about what to do.

Martha Gellhorn and Joris Ivens had their hands full in New York with the editing of Spanish Soil and its distribution in America. Martha took advantage of her acquaintance with Eleanor Roosevelt to suggest that he invite her and Hemingway to the White House to see it together. Although Martha and Joris repeatedly invited Hemingway to come to New York and work on the text for the documentary, Hemingway stayed on Bimini, trying to cheer up Pauline and fish.

It was only on 20 June, despite Pauline’s protests, that he took the train to New York and got to work. The text he was to write was to be spoken in the film by the “enfant terrible” Orson Welles , although Hemingway was not enthusiastic about the idea, as Welles came to the set with his own ideas. “What do you effeminate theatre-goers know about war?” rumbled Hemingway, which so infuriated Welles, who was a true giant, that he said, “Mr Hemingway, how strong and great are you?” They ended up drinking a bottle of whisky together.

But Martha’s efforts have borne fruit. On 8 July, Martha, Hemingway and Ivens were invited to the White House to show Spanish Soil to President Roosevelt and his wife after dinner. When the three arrived in Washington, Martha immediately bought three large sandwiches, saying that the White House dinner would be inedible anyway. She was right; the watery soup was followed by inedible boiled beef, a wilted salad and a dessert that someone must have given to the President.

Spanish soil was well received by the 30 or so invitees, but Roosevelt ended up saying that, however sympathetic he was to the cause, he could not lift the embargo on arms exports to the Republican government. From Washington, Hemingway, this time with Pauline, flew to Hollywood – Martha tactfully stayed in New York and began writing her book on Spain – where the film was enthusiastically received and after the screening they raised money for 15 ambulances for the Spanish Republic. Only Orson Welles’s voice in the film is said to be too honeyed and aristocratic for such a serious subject.

Back in New York, Hemingway finally submitted the manuscript of his novella, which he decided to publish as a stand-alone novel rather than with other stories under the title To Have and Have Not. Almost at the same time, he signed a new contract with NANO to report from Spain and was on a ship bound for Le Havre in August 1937. He decided to return from Europe with Martha only, and indeed Martha left shortly after him on another boat for Le Havre.

Hemingway had had enough of secret phone conversations, dubious letters and a separate life. When they met in Paris, they read the reports from the front and found them to be bad. The Republic was suffering defeat after defeat and the northern part of Spain seemed lost to it. What about the rest of the country? And which way should they go to Spain? At the beginning of September, they took a train to Barcelona and then a plane to Valencia. Through the plane windows, they saw the blue Mediterranean Sea and the black stain on it, stretching out where an Italian warship had sunk a British tanker flying the Spanish flag the day before.

They immediately left Valencia and managed to reach the fortified town of Belchite, which had been taken by the Republicans. All they saw were smoking ruins and an empty city, with nothing but stinking corpses lying in the streets. There was no accommodation and they had to fend for themselves. Near Teruel, they came across a group of guerrillas whose mission was to blow up the trains heading for Zaragoza. Years later, their commander, Pole Chrost, still remembered Hemigway’s snide remarks and his questions about guerrilla warfare.

The next day, they were asleep in Madrid at the Hotel Florida. They had chosen rooms 113 and 114, which were in a corner of the hotel, in fact in a dead corner, which protected them from the cannon shells. The air was already cooler and crisper, the autumn sun was warming the ruins of the buildings, food was hard to come by, imported spirits were no longer available, and only local wine and beer were mainly on tap. When the shelling started, everyone opened the windows to prevent the air blast from crushing the shutters. Rumours circulated that Franco would soon have to decide to attack the Castilian plateau and break through to Madrid.

Waiting in Paris

To Have and Have Not appeared on the shelves in mid-October, but the reviews were not good. Hemingway was in a bad mood and promised to remember the names of the critics. The news from the front was also bad. The Nationalists had taken Gijon, completing the takeover of northern Spain, and had staged a veritable massacre among the Republican troops, whose commanders had retreated with their Russian advisers. What comes next, perhaps Catalonia?

On a dark night in mid-December, two ships sailing in opposite directions collided in the middle of the North Atlantic. On the Normandie, sailing from France to New York, were, among other celebrities, Joris Ivens and Martha Gellhorn, who wanted to spend the Christmas holidays at home in St. Louis. On the other hand, the Europe ocean liner, with Pauline Hemingway on board, was sailing in the opposite direction from New York to Le Havre. For months she had heard rumours of an unfaithful husband, but now she wanted to spend the Christmas holidays with him in Paris and smooth things over so that they could be like they used to be.

It arrived in Paris on 21 December, when it was already lightly snowing. She arrived at her hotel, but there was no sign of Hemingway, who had assured her twice that he would be waiting for her. On 15 December, the Republicans attacked the Nationalist positions at Teruel. The Nationalists were as surprised by the winter attack as Hemingway, who was then in Barcelona, from where he intended to travel to Paris. He turned around and hurried to Valencia, from where it was only a few hours’ drive to Teruel.

The Republicans advanced quickly to the town, where 6 000 nationalists, along with civilian hostages, women and children, were entrenched. The first wave of Republican soldiers was closely followed by foreign journalists. It was bitterly cold, and to grab a rifle barrel meant that there was skin left behind. Two trucks of Asturian dynamiters also arrived, with bags full of dynamite hanging around their necks, clearing obstacles.

Hemingway was elated. This is what he had been waiting for, so he came to Spain to see real warfare. Pauline is waiting for him in Paris, so he should wait a little longer, because she will be a bother anyway. He spent the Christmas holidays in Barcelona in a bad mood, because the editors were unhappy with his reports on Teruel because they duplicated those of other correspondents, his liver was sore from drinking and he did not go to Paris until 28 December. At that time, both belligerents admitted that Teruel belonged to no one, because no one was the winner in this battle.

When he returned to Paris, he found Pauline on the verge of a nervous breakdown. She was on the verge of jealousy in his hotel room, raging, arguing and even threatening to jump off the balcony. “I didn’t want to leave Spain and I wish most of all that I could go back,” he admitted quietly. He was also a little jealous of Martha because her articles on Spain were well received.

But when he learned that the Nationalists had smashed the Republican troops in a strong offensive and were less than 50 kilometres from the Mediterranean Sea, he made a quick decision. He must go back and report. On 18 March 1938, he was already on a ship bound for France. Martha followed him on another ship as soon as she knew where he was going. She disembarked in Cherbourg on 28 March. She found the three-month separation from Hemingway difficult to bear and promised herself that one day she would write a story about lovers who are separated for a long time.

In Barcelona, they saw first-hand how chaotic the situation is. Every day, thousands of people die in hostile air strikes. France closed its border with Spain, then reopened it to a new shipment of arms, and it looked as if the Republicans would be defeated in a matter of weeks. Every morning they went to where the fiercest fighting was taking place. They drove on broken roads, past bomb craters and hid from air strikes. They saw the rubble, the bodies and felt the suffering of the people.

Then came the news that the Nationalists had penetrated to the sea at Vilarozo and cut Spain in two. Their commander dipped his toe in the sea and crossed himself. Rivers of refugees were already moving towards the French border.

On 24 April, the Spanish premiere of Spanish Soil took place in Barcelona in front of a packed house. After five minutes of screening, an air-raid alert was sounded, but no one left the auditorium. Everyone stood up and sang the Catalan anthem. When the lights came up, someone pointed to Hemingway and there was a five-minute applause.

The next day, Martha wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt: “What is happening here concerns all of us who do not want to live in a world whose bible would be Mein Kampf.”

Hemingway decided to go to Madrid, where a nationalist offensive could be expected. He and Martha travelled to Marseille, then she went on to Paris, he took a plane to Valencia and then a car to Madrid. The Hotel Florida was just as he had left it. He could not see anything new here, because there was a lull at the front, so he returned to Paris as soon as possible and then went to America. “I have neglected my family very much this year and I must make amends,” he wrote to a friend. Whether this was really possible was, of course, another question.

Pauline has already warned him not to go home if he thinks he’s going to do the same as last time. “If you are happy over there, go over there, and don’t come here if you are unhappy.” Martha stayed in Paris, watching Hemingway leave her again, and buried herself in her work. She interviewed the fascist Doriot and the communist Thorez, went to the Longchamp horse races with Aga Khan and drank champagne with Parisian cream.

Whom it rings

Hemingway’s homecoming was not a success. First, in New York, he accused NANA of withholding payment for his articles and of not appreciating that he had risked his life in the pursuit of his work, then immediately afterwards he travelled to Miami. Pauline met him at the airport and the ride home was a cold shower. No one mentioned Martha. At an intersection, he crashed into an oncoming car and, although no one was injured, he started shouting, screaming and swearing and did not stop even when the police arrived and arrested him. The judge immediately ruled that the damage was minor and released him.

When he wasn’t writing, he liked to go to New York to watch boxing matches. Once he came home from such a trip to find Pauline ready to go to a party and he refused to go with her, preferring instead to go to the room where he usually wrote. It was locked, and as he could not immediately find the key, he drew his revolver, growled and threatened to blow the door. He shot first at the ceiling, then at the door, broke the lock and locked himself in the room. Pauline stormed off in a rage to the party and Hemingway came after her a few hours later in a bad mood. He immediately got into an argument with a guest and started a fight. Pauline rushed home in despair.

Martha was still in Paris, convinced that it didn’t matter whether they were on the phone at home or he was calling her in Paris. In November 1938, the Nationalists launched a major offensive at the Ebro River and Hemingway was back in Barcelona. He knew that this was the last time he would be in Spain. He and the other journalists made their way along the roads and past empty fields. Grenades whistled around their heads and guards gestured with their hands for them to get back. Someone took them by boat across the Ebro to the house where Enrique Líٕster had his Republican headquarters. He looked tired, allowed himself to be photographed and repeatedly apologised for being called to the phone.

On their way back home, they met Republican reinforcements coming to Ebro. The soldiers, going to meet their deaths, raised their fists and cheered them on. On 6 November, Hemingway was taken from Barcelona to Ripoll, near the French border, where he said goodbye to Spain. He travelled to Paris and met Martha. She took him on board a ship bound for America, and she made another trip to Barcelona because she wanted to write about the suffering of the civilian population.

She visited hospitals, wrote about children lying in yards staring at her with dull eyes, about queues for food. She returned to Paris in early December, before the telephone lines to Barcelona were cut, wrote a series of articles for Collier’s and returned to New York, where Hemingway was waiting for her. She was not convinced that their relationship had a future and wanted to check it out.

When Pauline and Hemingway first arrived in Key West, it was a sleepy fishing town where one could write and think in peace. But the years had taken their toll and the highway brought crowds looking for fun. Pauline found many friends among them. The house was always full of them, guests splashing in the swimming pool, playing on the lawn and talking loudly. Hemingway did not like them. He missed Martha, he missed Spain, but above all he wanted to write in peace. But his beloved Spain was at the precipice. “War is all about getting it – and we didn’t do that,” he mused.

In February 1939, he invited Martha and her mother to Havana. He found a small one-storey villa called Finca Vigia, with a swimming pool and tennis court, and a garden from where he could see the lights of Havana in the distance at night. Here he conceived a novel, the basics of which he already knew; the smell of ammunition, the jokes fighters tell each other before battle, the story of guerrillas, of nurses raped, of flight and hiding, of bridges to be destroyed and of battles lost.

He took a new sheet of paper, prepared the typewriter and, while Martha was still asleep, wrote his first words: “We were lying in the woods on a brown floor strewn with pine needles.”

On 27 March 1939, Franco invaded Madrid. Before that, he issued a declaration of war: “Today our victorious troops have reached their objective.” Hemingway’s Spanish dream was over. The book he began to write in March 1939, which he eventually entitled For Whom the Bell Tolls, brought him the artistic and commercial success he had wanted for so many years. Was it a story with a happy ending for him?