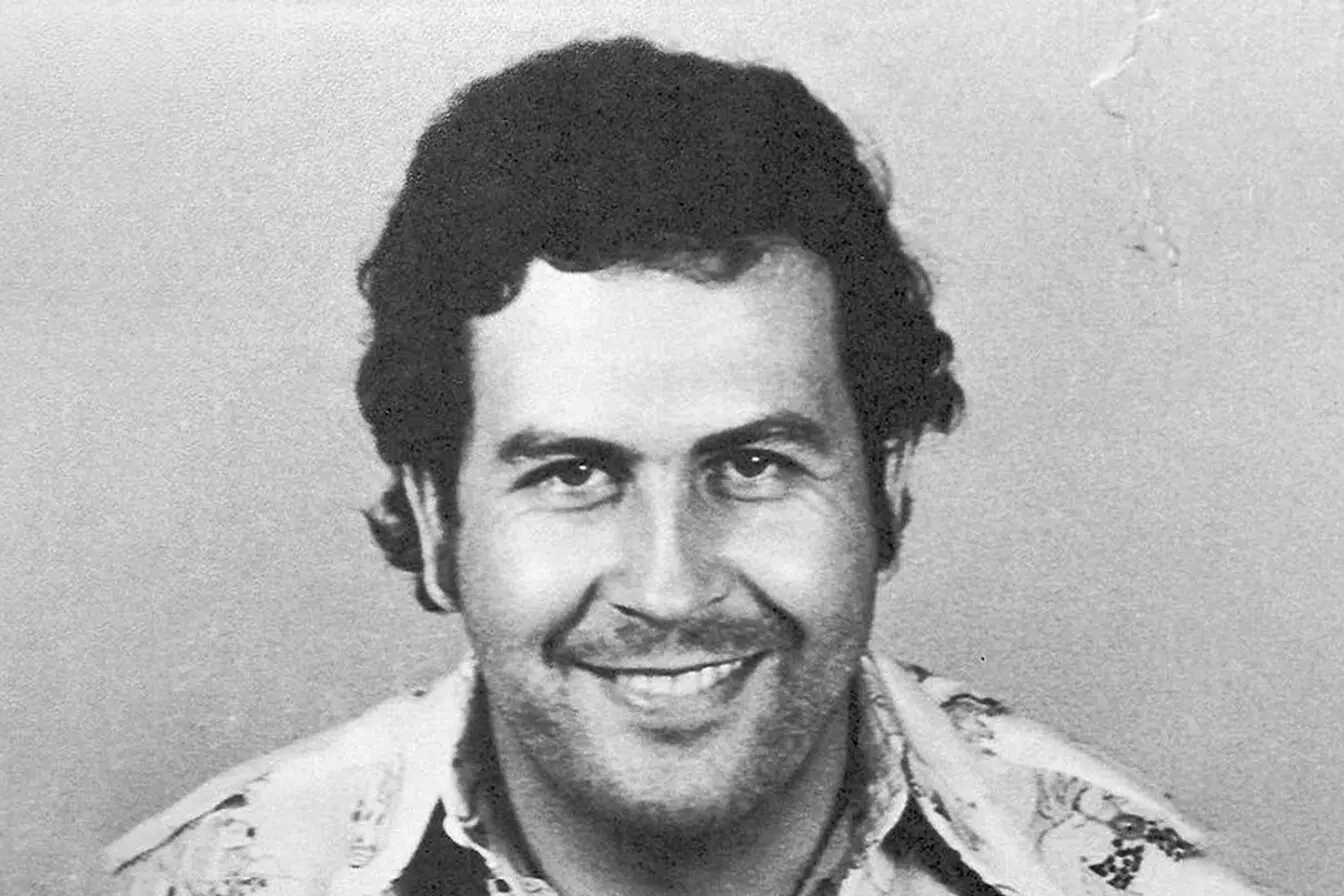

On the day Pablo Escobar was killed, his mother Hermilda was at the hospital for a medical check-up. When she heard what had happened, she fainted. When she recovered, she went straight to the Medellín district of Los Olivos, where journalists and television cameramen were already gathering. Crowds of people were pouring into the quarter, blocking the adjacent streets, the most curious climbing on to the roofs of the nearby low-rise houses, which were the most numerous in the quarter. The police tried to restrain the people and did not let them leave the scene. Some said that Pablo had really been killed, others that he had managed to escape. Many wished that he had really escaped and were convinced that the police would never catch him, that they could not catch him either with their death warrants or with US dollars. It could not be otherwise. Medellin was Pablo’s real home. Here he earned millions, here he used the money to build apartment complexes, housing for the poor, football pitches for the workers to enjoy themselves after a hard day’s work, he opened restaurants and discos.

Hermilda Escobar, a bony, grey-haired old woman, was pushing her way through the crowd when a policeman stopped her and refused to let her go on. “I am Pablo Escobar’s mother”, she spoke, but the policeman just remained silent. The crowd around began to murmur and shout at the policeman: “Don’t you have a mother?” The policeman backed away. Hermilda crossed the street and came to a small clearing in front of a house where a body lay with a bloody hole in the middle of its forehead. “Idiots!” she screamed, “that’s not my son. This is not Pablo Escobar. You killed the wrong man.”

The police pushed it aside and lowered the body of a fat man on a stretcher from the roof, his round face swollen and bleeding. At first it was hard to tell who it was, but then Hermilda fell silent and crossed herself. She felt relieved that the nightmare for her son was finally over. She showed no emotion as she left the place, only saying to the reporter: “Now I can finally rest.”

In April 1948, there was no more exciting place in South America than Bogotá. In this city of millions, the Inter-American Conference, supported by the United States, was meeting with the ambition of winning for the continent a more important place in the world. The conference also attracted many leftists to the city, including the young student Fidel Castro. They were opponents of this conference, which they considered to be a bow to the demands of the gringos. They were looking for a leader for their ideas and were convinced that they had found one in the 49-year-old Colombian politician Eliecer Gaitan.

“I am not a man, I am the people!” Gaitan dramatically shouted at his rallies. He was of mixed blood, highly educated, with the dark complexion and curly black hair of a Colombian Indian. Times were bad in Colombia, inflation was high and so was unemployment. In the villages, unemployment meant hunger and starvation. Protests, encouraged by Marxist agitators, became increasingly violent, and the responses of the landlords even more so. “I demand an end to the violence against the people!” Gaitan repeated in vain.

On the opening day of the Inter-American Conference, Gaitan left his office late in the evening with a small entourage to meet Fidel Castro. The group passed a fat, dirty and unshaven man, he let them pass, then caught up with them and pulled a revolver from his jacket. Gaitan turned and was about to run back into the building when Juan Roa shot him. Gaitan clung on as he was hit by three shots and died a few hours later in hospital after doctors tried in vain to save his life.

His assassination marked the beginning of Colombia’s modern history, and all hope for a peaceful future vanished. Riots broke out, whole neighbourhoods burned, Marxists wrapped red ribbons around their arms and dreamt that the revolution had begun, but soon realised that they could not control the masses. Castro had to take refuge in the Cuban embassy because the police were hunting down leftists. More than 200 people died and hundreds more were injured in the riots. Private and official armies then began to terrorise the countryside, the government fought guerrillas, industrialists fought trade unions, conservatives fought liberals, and bandits took every opportunity to loot.

Cocaine, the new drug of addiction

It was in this meteor shower that Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on 1 December 1949. He grew up with terror. Anyone can be a criminal and a terrorist, but as an outlaw, he must stand for something. Whatever the motives of the criminals in the mountains around Medellín, the vast majority of people watched their bloody dance with a kind of satisfaction. But while other criminals became local heroes, Pablo Escobar’s power transcended the state and became real. At the height of his power, he stole the Colombian state and in 1989 Forbes magazine declared him the seventh richest man on earth. He was a vicious thug, but he had a social conscience that in many ways masked his crimes.

Thousands mourned his death. In the funeral procession, people snatched the coffin from the hands of the pallbearers, tried to open the lid and touch his grey face. His grave is always decorated with flowers and is a popular tourist destination.

When Pablo was a little boy, his mother, who was a teacher, vowed in front of the statue of Jesus of Atocha that if he would keep the leftists and liberals away from him, her son would build him a chapel. Pablo did not grow up in poverty, as some journalists wrote. Although there was no electricity in the house, they had running water, a sign of the middle class. The hallmark of Colombia at that time was marijuana, nature’s golden gift. Pablo was addicted to it all his life.

Lucrecio Jaramillo did not complete his studies at the Lyceum, but instead turned to crime. He stole cars, dismantled them and sold them the same day for spare parts. He was not always lucky and was imprisoned several times. Then he started selling protection. People had to pay him not to steal their car. People who did not pay him, he simply kidnapped. If that didn’t help, he would kill them.

He was already a well-known and successful crook when he had the chance to strike it rich, as the world discovered the sweetness of cocaine. The illegal routes to North America that had been used for marijuana shipments were now being used for cocaine shipments. Cocaine will be what makes Pablo Escbar, the Ochoa brothers, Carlos Lehder and Roidriguez Gacha richer than they could have ever imagined. At the end of this decade, they controlled more than half of the cocaine that entered North America.

Cocaine has become Colombia’s biggest export, benefiting mayors, councillors, congressmen and presidents, police officers and the army. Cocaine brought so many dollars into the country that Pablo Escobar alone had 19 residences in Medellín, a number of yachts and planes at sea, real estate all over the world, apartment complexes and banks. He spent ten years building this empire. He was not an entrepreneur, because he did not know his way around an economy, but he was, simply put, more ruthless than the others. He eliminated his competitors without a second thought.

Rubin, a young pilot from Medellín, met Pablo in 1975. He had passed his pilot’s test in Miami and spoke excellent English. When some drug lords started to ship cocaine to America, he quickly got along with them. Soon he was buying and selling small planes and hiring pilots to fly between Colombia and North America.

Rubin was not a gangster, but he liked to live well. His boss in Medellín was Fabio Restrepo, who sent two 60-kilo shipments of cocaine to Miami every year. Pablo initially hired Rubin and Ochoa because he wanted to buy some cocaine from Restrepo. The two men met Restrepo in a small apartment in Medellín, bought 14 kilos of cocaine from him and the deal was done. For Restrepo, it was a small deal, and Pablo Escobar was an insignificant gangster. That is why everyone was surprised when Restrepo was killed two months later, and even more surprised when they found out that Rubin and Ochoa were now working for Pablo Escobar. There was no proof anywhere that Restrepo had been killed by Pablo Escobar.

Pablo married Maria Victoria Henao Vallejo in March 1976. The bride was 15 years old and so young that Pablo had to bribe the bishop to marry a minor. Three months later, government agents from the DAS (Administrative Department of Security) found 35 kilos of cocaine in the flat tyre of Pablo’s truck. Pablo could have been sentenced to several years in prison. He had to try twice to bribe a judge to get out of prison. The two agents who arrested him were soon found shot dead.

No one in Medellín complained about his methods, because they all made good money. He provided security for all cocaine distributors, controlled the transport routes and received a commission on every kilo of cocaine. When the coca grew, the leaves were processed by independent dealers and the cocaine shipments were added to the cargoes controlled by Pablo. He demanded a 10% commission on the price the cocaine fetched in North America. If a shipment was intercepted or otherwise lost in Colombia, Pablo would reimburse the owners. However, only the profit from one or two shipments arriving in Miami, Los Angeles or New York outweighed the losses that would have been incurred in Colombia.

With all the millions he earned, Pablo was able to buy protection for his cargo. Sometimes he could afford to have one of his shipments deliberately fall into the hands of the police, who of course saw it as a great success. He was the undisputed King of Medellín. He threw wild parties and beauty contests. Beauties had to strip naked and compete to see who could be the first to get hold of an expensive sports car, which then became her property. He also started travelling around Peru, Bolivia and Panama, buying companies that could benefit his business. But he was not the only one. A rival cartel from Cali was doing the same.

As his fortune grew, he wanted to improve his public image and denied any connection to the cocaine trade. He also sometimes used left-wing rhetoric when it suited him. The Marxist guerrillas of the FARC, the ELN and the new urban guerrilla called M-19 enjoyed the support of Colombian youth and students, and Pablo knew how to exploit this. He was also fascinated by the career of the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, who invaded Texas and New Mexico in 1916.

He paid his workers in the cocaine processing labs well and spent millions on social projects in Medellín. The conservative Catholic Church in the city supported his social programmes and some priests supported him throughout his life. He founded Medellin Without Slums, an organisation that raised money to build housing for the poor. He walked through the slums accompanied by local priests who gave blessings. He became a kind of local Robin Hood. And he did not forget to send tons of cocaine to North America.

He even bought a small submarine that could hold 2000 kilograms of cargo. It landed off the coast of Puerto Rico, where divers picked up the cargo and took it to Miami in fast boats. He sent small planes to America that could carry thousands of kilos of cocaine. He then bought an old Boeing 727 and removed the seats so that it could carry up to 10 000 kilograms of cargo on each flight.

Cocaine stirs America

In response to the real epidemic of cocaine use in the United States, President Reagan created the Cocaine Anti-Smuggling Division in early 1982. However, it was not until after George Bush took office that the department really began its work. But it was not until 1986 that cocaine was transformed overnight from a party drug at social gatherings into a killer drug. This was triggered by the death of the famous basketball player Len Bias, who collapsed dead from a cocaine overdose at a party.

Suddenly, stories of wild parties in Hollywood have shown their dark side. Cocaine lost its innocence when it started to be sold in the dark alleys of American cities and became a social problem. The US administration was particularly concerned about the alleged links between the drug cartels and Colombian left-wing guerrillas. “These guerrilla groups initially denied any connection with the narco-cartels and denounced the negative impact of cocaine on society. Now, however, some have become actively involved in the cocaine business, demanding monetary compensation from the narco cartels for protecting their coca plantations. Some groups have even started selling cocaine and using the proceeds to buy weapons,” the CIA report testified. The new US Ambassador, Lewis Tambs, on his arrival in Bogotá, said that as Ambassador to Colombia he had two priorities; drugs and Marxism.

With the approval of Colombia’s new Justice Minister, Lara, the Americans have started testing the use of herbicides to destroy coca plantations. Shortly afterwards, the police succeeded in destroying a large cocaine processing plant on the banks of the Yari River. The plant had 14 laboratories and employed 40 people. This was a major blow for the Medellin cartel. A month later, the Minister of Justice, Mr Lara, was killed while being chauffeured around Bogotá. A motorcyclist drove past and fired seven bullets at him. He refused to wear the bullet-proof vest given to him by the US ambassador, but before doing so, he made sure his family was given refuge in New York.

Killing him was Pablo’s mistake. Killing a Justice Minister is not just an act, it is an act of hostility against the state. Pablo Escobar thought it would be a good idea to go to Panama temporarily. This was a big change for him. Just a year before, he had been elected as a substitute in Parliament, he had a diplomatic passport, and now he was practically an exile.

He boarded a helicopter and flew to Panama, where other cartel leaders had taken temporary refuge. He did not know what their intentions were, but he immediately started negotiations to return to Colombia. He did not want to live anywhere else but Colombia. But even in Panama the ground became too hot for him and he quickly left for Nicaragua. There, according to American reports, he emerged in a very dramatic way.

Pilot and drug dealer Barry Seale is arrested by police in Miami. Facing a prison sentence of several decades, he agreed to work as an informant for the police. In June 1984, he flew to Managua in a C-124 to pick up a 750-kilogram shipment of cocaine. A camera hidden in the nose of the plane recorded Pablo Escobar and a Sandinista regime official supervising the loading of the cocaine onto the plane.

The news was a sensation in Washington and was seen as proof of the Marxist-Sandinista regime’s links to the Colombian drug cartel. Seal was assassinated two years later, shortly after he had unreasonably refused to enter the US witness protection programme. Pablo never forgot the betrayal.

Escobar soon returned home. Dangerous as this was for him, he decided to fight his battle at home. He never left Colombia again. His greatest fear was that he would be handed over to America. Four judges who had handled his case had already fallen under fire. In November 1985, a group of M-19 guerrillas stormed the Judicial Palace in Bogotá and demanded that the authorities repeal the law extraditing their citizens to America. The army surrounded the Palace of Justice and killed the guerrillas only after an indignant battle. Pablo allegedly paid the guerrilla group one million dollars to carry out the action.

Pablo then made a gesture of appeasement, hoping to mollify the authorities. He betrayed his long-time business friend Carlos Lehder, who was then arrested by the police and put on a plane to Miami in February 1987. There he was sentenced to 135 years in prison. But this did not reassure the United States. It still demanded Pablo Escobar’s extradition. In April 1986, President Reagan signed a presidential order allowing direct military action against the drug cartels.

In the summer of that year, US troops joined DEA (Drug Enforcement Agency) agents and Bolivian police to destroy fifteen cocaine processing laboratories in that country. But the murders in Colombia have continued almost daily and have even reached into Europe. The former Minister of Justice, now Ambassador to Hungary, was stopped in a snowstorm by strangers and shot five times in the face, but survived.

Meanwhile, Pablo lived quietly in his haciendas, preferably on the large Napoles estate. He was not afraid of police action, as he was always informed in advance. In 1989, the estate where he lived was attacked by a group of former elite SAS soldiers. The attack failed because one of the helicopters crashed into a nearby hill. The attack was attributed to his rivals in the Cali cartel.

But Pablo did not have a rosy future. Presidential candidate Luis Galan promised to rid the country of the drug cartels. He was killed while speaking at a campaign rally. Three months later, a bomb blew up a passenger plane, killing 110 innocent people, including two Americans. The new presidential candidate, Cesar Gaviria, was supposed to have been on the plane, but changed his mind at the last minute and did not go.

Killing popular politicians and the terrorist attack on the plane were serious mistakes by Pablo. This meant he was a direct threat to American citizens. This made him a legitimate target for Americans.

US intelligence arrives

At this time, Pablo Escobar was best known to Hugo Martinez, a Colombian police colonel, although they never met. He recognised his voice, knew his habits, when he went to bed, what he liked to eat, what music he listened to, what shoes he wore and what sexual preferences he had (preferring girls aged between 14 and 15). He also knew that the Americans were tightening the net around Pablo. While some of President Bush’s advisers thought that the time had come when their troops in Colombia should operate directly without the help of the Colombian police, Bush made it clear that they were to work with them.

That changed everything for Martinez. Within four months of Galán’s death, Colombia had handed over as many as 20 drug traffickers to the Americans. They also set up a special police unit based in Medellín, now commanded by Hugo Martinez and tasked with bringing in Rodriguez Gacha, the Ochoa brothers and Pablo Escobar. No one, not even Martinez, wanted to take command of this unit of 200 policemen, because it was playing with death. In just three weeks, 30 members of this unit died. They were killed on the roads on their way home, in the shops while they were shopping, at home during dinner.

Pablo quickly responded to the creation of this unit. A car bomb was discovered in the garage of the apartment building where Martinez was staying. All the occupants of the house were high-ranking police officers and only a few knew what Martinez was doing. Someone must have informed Pablo. The residents met and demanded that Martinez’s family move out. Then someone offered Hugo Martinez six million dollars if he would give up the hunt for Pablo Escobar.

In September 1989, an American curiously looked out of the window of his room at the Hilton and started counting explosions. The bombs, which in principle did little damage and were strategically placed outside the entrances to banks, government buildings, major state-owned companies, shopping malls and transport hubs, were going off all over the city. It lasted for hours. It was Pablo Escobar’s response to the President of Colombia’s attempt to destroy the Medellín Cartel and, at the same time, a clear message that Pablo could be present everywhere.

The American Steve Jacoby, who watched the explosions through the windows of the Hilton, was no ordinary traveller. He was part of a secret team called the Spike Centre, which came to the aid of the Colombian government and specialised in gathering operational intelligence; they counted how many windows and doors the building to be targeted had, what kind of weapons the guards had, where the target went to lunch and slept, what kind of cars he used, and so on. Their speciality was tapping telephones and radio transmitters.

The US embassy in Bogotá had several departments of various US intelligence agencies, and the CIA dealt mainly with Marxist guerrillas in the hills. The DEA worked closely with the Colombian police to detect coca plantations. The FBI infiltrated the cartel with information it had obtained in America and negotiated with those who were willing to surrender in exchange for light sentences. The Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Agency also had a representative in the American embassy.

The Spike Centre team worked almost invisibly in Bogotá. They avoided restaurants and bars, cooked their own meals and drove around the city in inconspicuous cars. Covert action was their strategy. The longer the target was unaware that he was being watched, the more information the group could gather. Only three people in the US embassy knew what the Spike Centre was doing, and the Colombian authorities were not even informed. The Americans only told them that they would tighten their control over the cartel.

Telecommunications have often been a weak point for criminals, guerrillas and terrorist organisations. But Centra Spike has always been two steps ahead of them. It used old Beechcraft six-passenger passenger planes, usually chartered for charter flights, but now their interiors were full of electronic eavesdropping equipment. As long as the target had a battery in his mobile phone, the phone could be activated from the plane to emit low-intensity frequencies. This made it possible to determine where the target was. They could also tap into the phone while the target was asleep and listen in on their morning conversations.

In the autumn of 1989, Americans did not know how the Medellin Cartel worked. Pablo Escobar was just one of the leaders. They had Rodriguez Gacha as the leader of the cartel and soon found out that he was regularly telephoning a woman. He was telephoning from a hacienda on top of a hill south-west of Bogotá. The Americans informed the Colombian air force that they had sent a group of bombers to the area. However, the squadron leader happened to notice that there was a village at the foot of the hill where a stray bomb could cause civilian casualties among the villagers. He called off the attack, but a little late, so that three bombers were already over the hacienda.

Rodriguez had just telephoned Gacha and the Spike Centre was listening in on his conversation when the bombers appeared over Gacha’s head. He immediately ran away. Whether the squadron commander called off the attack on purpose or for humanitarian reasons was never disclosed. But everyone knew that Gacha had excellent connections in the Colombian army.

The Spike Centre tracked down Gacha a week after he had taken refuge in a hut near the Panama border and telephoned his mistress in Bogotá. She was unable to establish the exact location. They had been led there by someone working for the Cali cartel. The Cali Cartel would have had much to gain from Gacho’s removal. The police and the army decided to attack. Just in case, there was also a US warship off the coast at the time, with Delta Force and SEALs on standby.

Colombian police attacked the hut with helicopters armed with heavy Israeli machine guns. Gacha, his minor son and five guards fled into a banana grove, where they died. But after Gacha’s death, something strange happened. An avalanche of phone calls from Pablo Escobar was triggered. His voice was deep and calm, he spoke in proper Spanish and rarely used dialect. From the conversations, the Spike Centre concluded that he was in fact the real leader of the cartel.

Hugo Martinez had a good relationship with the Spike Centre, but ran the campaigns independently. In the first months of 1990, he and his team repeatedly found Pablo’s hideouts, destroying laboratories and looting cocaine stocks. It was rumoured that in doing so, his men would throw captured criminals out of helicopters or simply shoot them. There was, of course, no evidence of this.

Pablo Escobar immediately suspected that he had a traitor in his ranks, because too many of his laboratories had been attacked and too many coca stocks destroyed for this to be a coincidence. He tortured and killed several of his security guards, but to no avail. His life became a nightmare. Hugo Martinez came dangerously close to him on several occasions and he had to flee, his organisation slowly disintegrating.

My husband, who until a year ago had dozens of villas at his disposal, sometimes had to sleep in the woods at night. He no longer dared to use the telephone or the radio, and relied only on couriers. He had neither the time nor the resources to control his cocaine business, and he was losing large sums of money every month. At the end of 1990, he realised that the only way to save himself was to make a deal with the Colombian government. On his own terms, of course. He used his lawyer, Parra, as an intermediary, but Pablo was really afraid of him. “I won’t be killed by the police, I’ll be killed by Pablo Escobar because I know too much”, he liked to tell his friends.

Pablo in a luxury prison

To bolster his case in negotiations with the Colombian government, Escobar announced that he would kill two of his hostages. At the beginning of 1991, the grey-haired Marina Montoya was tied with a sack over her head and driven from place to place. She was first held hostage for four months and then shot six times in the head. Fiana Turbay died ten days later when the police raided the place where she was being held hostage.

The killing of two famous and popular women has had its intended effect. The deal between Pablo Escobar and the Colombian government, which the United States has called an unprecedented scandal, has been concluded. Pablo will surrender and will be imprisoned in a specially built jail in the mountains above Medellín, awaiting trial that could take years. Before he is sentenced, he will be released under a regular pardon.

Escobar thus emerged from his hiding place and went to the agreed location, from where he was to be taken by helicopter to “his” prison. His lawyers have managed to arrange for all airspace on the route to be closed at short notice.

After a short ride, the helicopter landed on a football field next to the prison. It was built on top of the Catedral mountain, with a beautiful view of the valley and the city of Medellin. Pablo personally supervised its construction and buried some machine guns and pistols nearby, convinced that they would come in handy. When he stepped out of the helicopter, he was met by fifty armed guards. These were the municipal orderlies of Medellín, the city he was overseeing. In fact, they were his employees.

In prison, he had all the comforts he needed; a large bedroom, a living room with a TV, an office, a jacuzzi, a gym, and special cooking facilities. He was able to go to football matches in Medellín and was also seen in a nightclub. He was also the only prisoner in this luxury prison.

While he was enjoying life in his luxury prison, the Colombian government was preparing his trial. The “Escobar problem” was assigned to a young lawyer, Eduardo Mendoza, who was promoted to Deputy Minister of Justice precisely because of this case. Above all, Pablo had to be transferred to a real prison. The police checked everything that came into Pablo’s luxury dungeon; drinks, whiskey, liqueurs, expensive meals, films, prostitutes and money, but they did nothing.

Pablo was very careful when communicating and mainly used carrier pigeons for messages, but other employees were able to tell that his dungeon was actually a large business centre. Throughout his time in this luxury prison, the United States, its embassy and the American press have been insisting that this farce must be brought to an end. What a prison, it is, after all, a centre for the consumption and sale of drugs.

On 21 July 1992, Eduardo Mendoza was summoned to the Presidential Palace in Bogotá and told that 400 soldiers had surrounded Pablo’s prison, and that his task was to notify the prisoner that he was to be transferred to a real prison. This was a violation of the agreement between the government and Pablo, but it could be forgotten.

Mendoza boarded a plane and flew from Bogotá to Medellin, from where he was driven in a military car up a narrow dusty road to Pablo’s prison. Meanwhile, it was already dark. The commander of the military unit surrounding Pablo’s dungeon, when asked by Mendoza why they were not breaking into the dungeon, replied that he had no such order, and an agonising argument ensued.

Meanwhile, a group of people appeared in front of the dungeon, apparently guarding a fat man in their midst. Mendoza knew it was Pablo Escobar. Pablo walked up to him, shook his hand and said: ‘You have betrayed me, and the President has betrayed me. But you will pay dearly for this. You will hand me over to Bush so that he can parade me around before the elections, as he did with Manuel Noriega, and I will not allow it. Maybe you will kill me. You will take me away and kill me. But before you do that, a lot of people will die.”

Before Mendoza could respond, a group of armed men surrounded him, threatened him and then imprisoned him in a room in Pablo’s prison.

“You cannot escape, you are surrounded by a large army,” Mendoza assured Pablo Escobar. Mendoza coldly replied, “You still don’t understand anything. All these people are working for me.”

An hour later, the sound of gunfire and bombs bursting was heard. Someone said to Mendoza: “Get out and run if you value your life.” Mendoza ran out into the open and down the slope until he reached safety. Meanwhile, the army had finished attacking the dungeon. It had killed only one man, some were wounded, but Pablo Escobar was nowhere to be found.

On the morning of 22 July 1992, the US Ambassador to Bogotá, Morris Busby, spending the weekend at his house in Maryland, was awakened by two phone calls. Both were from Bogotá. The first informed him that the Colombian President had finally decided to transfer Pablo Escobar to a real prison, the second that the prisoner had escaped. The Ambassador immediately returned to Bogotá. Perhaps this is the opportunity he has been waiting for. Finally, Pablo Escobar became a pariah, hunted by the police and pursued by the Americans. He was a poacher who could be shot by anyone.

The investigation showed that Pablo Escobar simply walked out of the dungeon and was not stopped by any of the soldiers. The leader of the military unit that surrounded his prison excused himself by saying that he had no orders to arrest the prisoner.

The Colombian government was now at a crossroads and decided to ask the “gringos” for technical assistance. They responded quickly and sent everything they had to Medellin. The Air Force sent converted RC-135s and C-130s, the Navy sent P-3 spy planes, the CIA sent its twin-prop De Havillands, and the CIA sent its latest product, a plane with PLIR technology that could shoot in the dark and through clouds. All these planes, which controlled the skies over Medellín, caused chaos in regular air traffic.

One day, one of them flew so low over the houses that journalists filmed the markings on it. A huge scandal broke out as no one could officially explain what the unidentified planes were doing in the Colombian skies. Over the next six months, more than a hundred Americans took part in the secret hunt for Pablo Escobar.

Los Pepes

In October 1992, Hugo Martinez made one of the big throws. “Tyson” Munoz, one of Pablo’s most successful assassins, was killed in a fight with the police. Someone had betrayed him and the police found a heavy metal door outside his apartment. They blew them up, but used too much explosives. The door flew all the way through the interior of the apartment and broke through its outer wall, ending up six floors down in the street. Munoz tried to escape through a back window where the fire escape was located, but he was arrested and while being held, one of the police officers sent a bullet into his forehead.

Pablo’s reply took almost three months. On 30 January 1993, a large bomb exploded outside the entrance to a shopping centre where mothers and their children were buying school supplies for the new school term, killing 21 people. Shattered limbs and body parts, including those of children, lay everywhere. “We will kill this son of a bitch if it is the last thing we do in the world”, said the head of the CIA section at the US embassy, as he watched the carnage.

But just a few days after the explosion, someone set fire to the hacienda La Critalina, which belonged to Pablo’s mother. Then, two bombs exploded in front of an apartment block where some of Pablo’s relatives lived. Then another of Pablo’s country homes was set on fire. All this affected people who, although not criminals, were in some way linked to Pablo Escobar.

The Colombian police were convinced that this was the work of individuals united in the Los Pepes organisation, people who had been persecuted by Pablo Escobar and had sworn revenge against him. Los Pepes wanted revenge against Pablo, his family and his associates. Over the years, many descendants of the victims of Pablo’s senseless murders had accumulated, so the desire for revenge was also great.

In the following weeks, the bodies of Pablo’s colleagues were found everywhere in Medellín and Bogotá. Many were convinced that this organisation was run by the Moncada and Galeano families, and that there were many police officers among them who wanted revenge for their fallen colleagues. The soul of the organisation was said to be Dolly Moncada, who wanted revenge on Pablo for the murder of her brother. She agreed with the authorities to tell them everything she knew about Pablo Escobar and to hand over her assets to the State for protection and refuge in the United States.

The hunt is over

At the beginning of February 1993, Pablo wanted to get his two children to safety in Miami. They had visas to enter the US and, as they were not criminals, there was no legal reason why they should not go. But the law forbade unaccompanied minors to travel abroad. The US embassy was strongly opposed to the departure of the children of a criminal whom it wanted to see dead. The children arrived at the airport accompanied by armed security guards, and had already boarded the plane with their escort when the police arrived. Some of the security guards were arrested, others fled and the two children were dragged off the plane. The following day, the US Embassy announced that the children’s visas had been cancelled because Pablo Escobar and his wife had not applied for them in person at the Embassy.

Now Pablo knew how hard the Americans were breathing down his neck. Then Los Pepes and the police got their hands on his lawyers. The police arrested some of them, and later the lawyers complained that they had been threatened. Some of the lawyers were murdered, horribly tortured, and a note was pinned to their bodies with new threats against other lawyers and the signature of Los Pepes.

In July 1993, Los Pepes kidnapped Pablo’s breeding stallion, worth millions of dollars. Later, our horse’s trainer was murdered, and a few weeks later the horse was tied to a tree, healthy but rendered infertile.

In late spring, the Spike Centre brought Hugo Martinez a tape of Pablo’s telephone conversation with his son. Martinez knew that Pablo would be difficult to catch without the help of the Americans. They were the only ones who had the necessary equipment to eavesdrop on the conversations.

So the Americans brought hand-held radios, no bigger than a suitcase, to Medellin. They were placed in vehicles parked at the foot of the hills around Medellin, where Pablo was believed to be hiding. Unfortunately, this equipment, designed to trace calls in open terrain, did not work in the hustle and bustle of the city, where many signals were intertwined. Pablo had long since stopped using mobile phones, only secure radios. From the many hills around Medellín, he could see the Altos de Campertre apartment house where his family lived, heavily guarded in fear of Los Pepes. This was Pablo’s weak point, which Hugo Martinez wanted to exploit, using the new American equipment.

Pablo’s 16-year-old son Juan Pablo was now the head of the family. He used binoculars to observe what was happening on the street outside the apartment building, note down the registration numbers of suspicious cars and take pictures of strangers who stopped in front of the house for no reason. Once, he saw two strangers get out of a car and fire a rocket towards the house. Nobody was hurt, but it was a warning.

The public prosecutor who officially visited the family later said that he saw what looked like a radio receiver in the next room. Several attempts were made to find out where Pablo was calling his son from. In a lightning campaign, the police raided several locations, but always found that Pablo Escobar was not there, although he was, but managed to escape in time. “We will get him soon”, Hugo Martinez was convinced.

It was increasingly clear that Pablo was now about his fingernails. Most of his associates were imprisoned or killed, he no longer had control over his business, and his cash was drying up. He had to sell his businesses, including shares in other companies, his art collections and jewels, all his real estate in Miami and most of it in Colombia. Much of this selling was done through his son Juan Pablo, who became his main link with the outside world. Juan Pablo acted as his father’s protector, guardian, defender and successor.

At the end of November 1993, the US Embassy learned that Pablo’s wife and children wanted to flee Colombia for London or Frankfurt. The whole family was protected from Los Pepes by the Colombian state, but at the same time the Colombian state was also keeping them under surveillance, putting pressure on Pablo to surrender and threatening that the protection would soon be gone. But no one wanted Pablo alive, not the police, not the Americans, not his former colleagues, not the Cali cartel. PABLO MUST THEREFORE DIE.

Pablo’s wife had already bought plane tickets to both London and Frankfurt, but somehow the journalists found out about the planned escape and the family was met at Bogotá airport by almost 100 journalists. The family boarded a plane bound for Frankfurt with an undercover US DEA agent. When the plane landed in Frankfurt, it had to park in a remote part of the airport for security reasons. The German authorities rejected the family’s asylum request and put them on a flight back to Bogotá. The family was accompanied by four other agents of the German emigration office on their way to Bogotá. In Bogotá, all the family members were taken to the Hotel Tequendama.

Over the next four days, Pablo from Medellín called his son at the hotel six times and demanded that he get the family out of Colombia by any means necessary. This time, US intelligence was able to establish where the calls were coming from. Pablo was calling from a moving car in the Los Olivos neighbourhood of Medellín. It was a large neighbourhood dominated by two-storey houses with small courtyards and gardens.

Pablo lived in a simple two-storey house with a small clearing in front of a palm tree. Since he had been on the run, he had become very thin. Most of the time he was lying down, eating, sleeping and talking on the radio. His time was occasionally cut short by hired under-age prostitutes. On 2 December 1993, he got up late, ate breakfast and waited. Only his bodyguard Limon was with him. His courier and cook were out running errands. In the afternoon he called his son.

Hugo Martinez, camped on the outskirts of Medellín with 35 of his most loyal men, was immediately informed of the call. The young Juan Pablo told his father that a journalist was harassing him with 40 questions. Pablo Escobar knew how important it was to have good relations with journalists, so he listened calmly as his son listed the questions.

Meanwhile, Hugo Martinez got into his car and drove to the Los Olivos neighbourhood, his men following unnoticed. The voice in Martinez’s earphones grew louder and louder, and he knew he was close. He reached a block of low-rise houses and knew that Pablo Escobar was in one of them. But which one? He circled the block several times until he saw a fat man with long hair and a beard on the second floor, talking on the phone. It was Pablo Escobar.

He immediately informed his men, and two of them immediately positioned themselves on either side of the front door to the house. The door was made of metal and had to be smashed with heavy hammers. Five men immediately burst into the house and the sound of gunfire was heard. The first floor was empty. Pablo’s bodyguard, Limon, as soon as he heard the rumble, jumped from the back window onto the brick roof and started running. He was hit by a hail of bullets and fell off the roof into the clearing in front of the house.

Then Pablo came, jumped on the roof, saw what had happened to the guard, squeezed himself against the wall where he had at least a little protection, and started moving towards a side street. In a hail of bullets, he collapsed on top of the roof. The shooting continued as in a real battle until the order came to cease fire. Someone found a ladder and the soldiers climbed up onto the roof. They turned over the body, which was lying on its stomach. A puffy, bloody face appeared. A soldier stood up and shouted to the others in the clearing: ” Long live Colombia! We killed Pablo Escobar!”

Later, Pablo Escobar was heard to come to the roof, holding a revolver in each hand and shouting, “Fucking police!” An autopsy showed that he had been hit by three bullets; one in the right leg, one in the back below the shoulder, and a third through the brain. His mother, Hermilda Escobar, predicted a dark future after her son’s death: “God save us from what will happen. Many terrible things will happen to those who sold him. I forgive them. I forgive with all my heart those who have wronged me and taken my son away from me. I forgive them.”

A journalist asked her if she would avenge her son’s death. “His death will be avenged, but I ask God to help my son’s killers not to go through the hell we have gone through.”