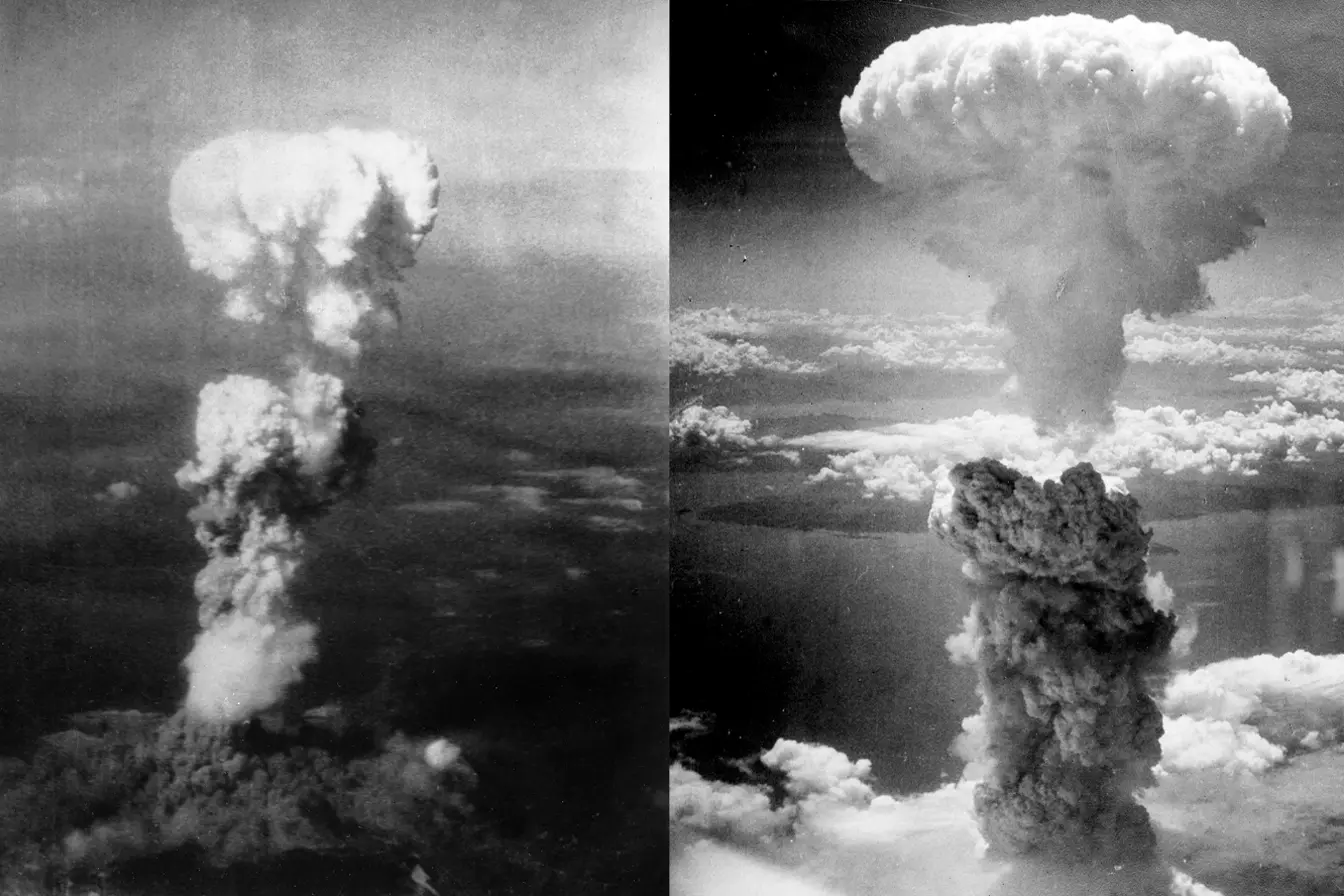

JANCFU, an unidentified US soldier wrote on the yellow casing. The abbreviation was an acronym for Joint Army Navy Civilian Fuckup. The crew of the B-29 Bockscar bomber signed the casing and added messages such as A second kiss for Hirohito or Here you go! Then they loaded the atomic bomb, dubbed Fat Man or Fat Man, onto the plane. A few hours later, on 9 August 1945, part of Nagasaki was leveled. Between 40,000 and 75,000 civilians died immediately or over the next few weeks. The bombing three days earlier had extinguished some 140,000 lives in Hiroshima. Several hundred thousand survivors suffered the long-term consequences of exposure to radioactive radiation for the rest of their short or long lives. The kiss of the combined US Army, Navy and civilians was cold but hot, and dead but fierce.

The top of the US military has calculated that the kiss of death is worth it. If he had tried to defeat the Japanese army in the conventional way, he estimated that it would have cost him hundreds of thousands of American military lives; if he had caused chaos with the new bombs and instilled fear in Japanese civilians that a hitherto unseen catastrophe might befall other Japanese cities, he would have ended the war for himself much more cheaply.

There is no consensus today on whether the American kiss of death was justified or not, but the survivors of the atomic bombs are unanimous: no one should experience such hell again. Even at an average age of over 80, their stories are a constant reminder of the lethality of nuclear weapons. They are by no means alone in their efforts. Just this year, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in Oslo to ICAN, the International Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Setsuko Thurlow, one of the survivors of the Hiroshima bombing, accepted the award alongside the Executive Director.

The narcissistic US President Donald Trump is predictably deaf to this ear, but there is much that he will never be able to understand or feel as a human being. Eight other world leaders have reportedly refused to give up nuclear weapons, even though the United Nations has banned them. They know the consequences of a nuclear explosion. The American soldiers who wrote sarcastic messages on the atomic bomb during the Second World War knew nothing about them. At that time, even the experts were wandering in the dark. It was not until two years after the end of the war that the Americans set up the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), which collected information on the effects of radioactive radiation in the field, but did not help or treat patients.

They also blew close behind the necks of their Japanese counterparts, with whom, in theory, they should have been cooperating. The Japanese, used to sharing their findings with colleagues and using them to make progress, would have revealed the truth to the world. For the Americans, the truth was a skeleton that had to remain in a tightly closed cupboard.

The world was only shown the physical devastation caused by the two bombs, innocent survivors were silent as the grave, and journalists and experts were silenced. After the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945, complete control was imposed on the coverage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A few personal stories came out, but far too few to give Japanese, American and other civilians around the world any idea of the scale of the catastrophe. The iron curtain of enforced silence was lifted only in 1952, when the Americans withdrew from Japan.

Hiroshima is no more

By then, many of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were already dead, and the survivors, known as hibakusha, were mostly silent. The American cover-up of the truth has perfectly fertilised the fertile soil of prejudice. The Japanese knew of the atomic bomb only as a new and devastating weapon, and the consequences of exposure to radioactive radiation were more alien to them than the most exotic of places.

Having survived the hell that many have described as the day of the explosion and the weeks that followed, the Hibakusha have, because of ignorance and the prejudice it engenders, hit another wall of discrimination. Those who were not betrayed by a body that had been burnt, cut by flying glass fragments or damaged by debris lifted into the air by the detonation kept their experience silent for practical reasons.

They did not want to risk not getting a job because many Japanese believed they carried diseases. And not that they would be left alone. In the 1950s and 1960s, many parents who had not lived through Hiroshima or Nagasaki did not allow their children to marry a hibakusha because they were worried that the children would be born deformed. To this day, however, specialists are monitoring the children of hibakusha to see whether they will get the same cancer as their parents. They are too young to know for sure.

Some remained silent simply because they did not want to remember. They never wanted to see again the horrific scenes they witnessed, nor to relive the feelings they felt when a single bomb destroyed their home, their city and their lives, even if only in their minds. For too many, it took many loved ones.

Fourteen-year-old Sadao Yamamoto was in his second year at Hiroshima Junior High School in 1945. Like all seniors, he had to work for the army. He and his first-year classmates helped to demolish buildings to create separate fire-fighting areas. On 6 August, the second-year students were working near the railway station, about 2.5 kilometres from the centre of the explosion, and the first-year students were working on the riverbank, about 600 metres from the site of the explosion.

At 8.15 a.m., Sadao Yamamoto heard and saw three B-29 bombers overhead. He did not know that one of them, the Enola Gay, was carrying a nuclear bomb. And he did not know that a month earlier, Hiroshima had been shortlisted as one of 17 Japanese cities to be bombed with the first nuclear bomb. In the end, as Japan’s seventh largest city, with a population of around 350 000 at the time, it was the ungrateful winner of the “bomb” competition.

It had everything it needed to win: a war industry that needed to be destroyed, it was flat so the atomic bomb could reach its full potential, and the Americans hadn’t bombed it much yet so its effect could be monitored without unwanted interference.

They have seen utter devastation. The city was “like a desert, except for the heaps of bricks and roofing tiles. I had to redefine the meaning of the word destruction or choose another word to describe what I saw. Perhaps devastation would have been more appropriate, but I really don’t know any word or words to describe what I saw”, recalled Michikiko Hachiya, a doctor. After the Little Boy bomb exploded, Hiroshima was simply gone. It didn’t exist.

Sadao Yamamoto also did not know that Enola Gay pilot Paul Tibbets would only drop his deadly payload when he saw the target, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. He could not rely on the accuracy of the radar, but had to select the target by eye. Sadao was therefore not particularly alarmed when he saw three planes coming from the south-east, the only thing that seemed a bit odd was that they flew over the city and turned around. Before he could stop to think, he heard a drumming explosion.

An extreme heat wave threw him to the ground. He lost consciousness. When he came to, he saw a “giant pink tower of fire” in the direction of the railway station. He thought that a bomb had hit the station. The left side of his face was burning. It was burnt. They put vegetable oil on it, which was the treatment for burns at that time. The teachers also treated other children who were burnt, but they did not know what to do with them. At that moment, they were as helpless as they were.

Sadao and some of his classmates took refuge in a shrine on a nearby hill. The forest seemed safe to him. He was waiting for another bomb. There wasn’t. He stepped out into the open. Instead of a city, all he saw was white smoke. After a while he could make out burning houses and buildings. Hiroshima was in flames.

His house was destroyed. His family survived because they were not at home, but his classmates who worked on the waterfront did not. All 321 first-year students died. The bomb exploded 600 metres above the ground because physicists had calculated that an explosion at that height would be most destructively effective. The temperature on the ground reached between 3000 and 4000 degrees Celsius.

People who were at the scene of the explosion were charred. People a little further away were badly burned. Skin was peeling away from their bodies. They were injured by the debris that flew through the air with tremendous force when it detonated, and others were stabbed in their bodies by glass fragments. Many jumped into the river and drowned before the fire that raged through Hiroshima.

On that day, 8187 students and 176 teachers worked for the army, Sadao later recalled. 6129 students and 132 teachers died, or 77 per cent of all the youth mobilised. The girls’ school was the hardest hit: all first and second year pupils, or 544 girls, died.

Between 60,000 and 90,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed. Burned and wounded survivors tried to find homes and relatives, but had nowhere to find their way in the infernal chaos. Everything was destroyed. They desperately tried to find water and, in the following days, food. Those who could, turned to relatives. Some had nowhere to go. There was no more housing in Hiroshima and no medical care.

Meeting the nuclear bomb twice

Twenty-nine-year-old engineer Tsutomo Yamaguchi, who designed tankers for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, saw none of that. He was no longer in Hiroshima, even though he was there on official business when the bomb exploded. He was about three kilometres from the centre of the explosion.

He lost consciousness. When he came to, he heard almost nothing. Both his eardrums had burst. The left side of his body was burnt. He took refuge in a shelter and spent the night there. In the morning, he wanted to go home to Nagasaki. He boarded one of the few trains that still linked the two cities. With his burns tended to, he went to work two days later.

He described what had happened to his boss. He didn’t believe him. He reminded him that he was an engineer. That he had to look at the facts. To calculate what is probable and what is not. And it didn’t seem at all likely to him that a single bomb would destroy a city.

It was then that Tsutomo saw the brilliant light again. The story repeated itself: another explosion went off and he survived again. He rushed home. His wife and his son of a few months were alive, but his home was destroyed. He spent a week in a shelter with his family before starting to rebuild his life in a destroyed Nagasaki. His hair fell out but grew back. He lost the hearing in his left ear. His skin, which was exposed to extremely high temperatures twice in three days, took years to heal.

Yet Tsutomo has made a full recovery. He and his wife had a daughter and she was healthy. He did not talk about what he had experienced. He expressed himself through songs until the situation changed and he too became a fervent supporter of the nuclear ban, and he put pressure on the Japanese Government, even if it was only a formality.

Two years after the explosion, doctors began to notice that hibakusha were more likely to get leukaemia and other cancers than the general population, but the Japanese government did nothing for them, even though many of those affected had no money for treatment. The bombing left them homeless and without possessions. They were more or less homeless.

For the first ten years, they were on their own and dependent on individual help, but then they banded together, raised their voices and forced the Japanese government to pass a law in 1957 to make their lives a little bit easier. This was also the start of a movement to force the Japanese government to admit that their physical and mental problems and their poor social situation were the result of the atomic bomb.

By law, the government has agreed to cover almost all their medical and dental services. If they could prove that they were two kilometres or less from the blast centre at the time of the explosion, they received an additional $1 000 a month in cash compensation, because this meant that they had been exposed to medium to high levels of radiation.

But it has been difficult to get status. The bureaucratic process was complicated and incomprehensible, and it was difficult to prove the exact location at any given time. As a result, some 90 per cent of survivors had their medical costs covered, and only about 10 per cent received a monthly allowance. Two years ago, there were still around 200,000 beneficiaries of government assistance.

The Japanese government also paid for Tsuto Yamaguchi’s treatment. The fact that he survived two explosions was irrelevant to her because, in her view, it did not affect his status and benefits. Nevertheless, when he became involved in the public campaign against nuclear weapons, he demanded that the government recognise his status as a double hibakusha, or survivor of two nuclear bombings. In 2009, he became the first person to be officially recognised as such by the Japanese Government, although he was by no means the only one with a similar experience.

Father’s skull

Tsutomo Yamaguchi died just a year later, aged 93, without ever knowing why the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, when it was not even on the shortlist for bombing. Kokura should have been leveled after Kyoto, Yokohama and Niigata were eliminated, but inexplicably Nagasaki emerged as a replacement target. It was anything but ideal: mountainous and bombed several times already, it did not allow for a clinically clear observation of the consequences of the atomic bomb, nor for a full unleashing of its power.

On 9 August 1945, pilot Charles W. Sweeny set off for Kokura in his B-26 bomber, named Bockscar. It was covered by clouds or perhaps smoke. He could not see the target and he could not rely on radar. The Japanese spotted him and greeted him with anti-aircraft fire. He flew on. The sky over Nagasaki was not clear either, but at one point he thought he saw his target, the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works. He missed it, but by a lucky coincidence, just enough to destroy the Mitsubishi-Urakami Torpedo Works, which was a little further north.

The bomb exploded at just after 11:00. Sixteen-year-old Yoshitoshi Fukahori had to work, as all students had to do at that time. At the sound of the explosion, he hid under his desk, as he had been taught. The office suddenly ran out of air, but he made it out unscathed. He went home.

Soon he no longer knew where he was. Everything was destroyed, he had nothing to find his way around. He stood there and finally spotted the ruins of Urakami Cathedral, once Asia’s largest Catholic cathedral, standing at the heart of Japan’s oldest Christian community, as a point of reference. People were coming towards him, fleeing from the centre. Their clothes were tattered and covered in dark ash.

They were holding on to his legs for a sip of water. The 16-year-old handed the bottle to one, then the other. “It was a mistake. More came, their mouths were open. I got scared and ran away.” He grabbed the arm of a woman who was clinging to his leg. He pulled a strip of her skin off.

Eleven-year-old Yoshiro Yamawaki was sitting in the living room with his twin brother when an unusual light lit up the sky over Nagasaki. They were alone. Because a bomb had fallen near their house during the last American bombing of the city, their mother and her four younger children had taken refuge with their mother for safety, while their father and 14-year-old brother worked.

The twins had moved into the room from the veranda of their home, 2.2 kilometres from the centre of the explosion, just five minutes before the white-blue light flashed in. They quickly threw themselves on the floor. They covered their eyes and ears, as they had been taught to do at school.

Debris started falling on them and they just wouldn’t stop. A few minutes later, Yoshiro heard voices from the street. He raised his head cautiously. He no longer recognised anything. The furniture was scattered around, the floor was covered with rubble and dirt. The ceiling was gone. From the floor he could see the sky. Pieces of glass had been driven into the walls. If he and his brother hadn’t got down on the floor, they would have been stabbed. And if they hadn’t become hungry just five minutes before the explosion, they could have been dead, or at least burned.

The twins took refuge in a shelter. About an hour later, their older brother found them there and moved them to a larger shelter nearby. It was full of mothers and their children. Those who were out in the open during the explosion were burned. Others were crying because they had been hit by shards of glass, others were injured by objects thrown into the air by the detonation.

The brothers waited all night for their father, and in the morning they went to look for him themselves. The closer they got to the centre of the explosion, the more everything was burnt. Even the trees and power poles were charred. Only the strongest pillars of the factories remained, the houses were destroyed. Bodies were seen among the rubble. Their faces, hands and feet were blackened and colourless. They looked like rubber dolls. When they stepped on them, their skin peeled off.

They saw dead bodies in the river. Their eyes were drawn to a girl, behind whom something white was writhing. They thought it was a scarf. It was her entrails. Nausea overcame them. They quickly headed towards the factory. Just in front of it, one of the brothers shouted. He saw the body of a boy who seemed to be vomiting noodles. There were fungi crawling out of his mouth.

They fled. They could hardly stop themselves from vomiting. They found my father in the factory. Or his body. The survivors advised them to cremate him there and take the ashes home. The crematorium was also destroyed. They collected wood and put my father’s body on it. When the flames licked him, they noticed that the foot was not well covered. They could not stand any more.

Let them go home and come back in the morning for ashes, they were again advised, seeing how difficult it was for them to cope with an emotionally unbearable situation. They went. At home, among the rubble, they found a container in which they decided to put their father’s remains. They returned in the morning. They experienced a new shock. The corpse had only partially burned. It looked like a skeleton covered in ashes. It was even more horrifying than the corpses they had encountered on the road. On top of that, it belonged to their father, the one with whom they had talked and with whom they had shared the table.

Yoshiro couldn’t bear the sight of him. Let’s go home and leave the body, he told his brothers, even though he knew it was wrong. The elder brother winced and decided to take the skull with them. He had a pair of pliers in his hand. He touched the skull. It crumbled. Inside was a half-charred brain. The brother screamed and let go of the pliers. He ran away and the twins followed him. They left their father’s corpse, but they were not the only ones who were forced to do so. Many more in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were unable to bury their loved ones.

The scene has haunted Yoshiro ever since. When he saw something like a skull, he thought of his father’s. When he saw something like a white scarf, he remembered the girl from the river. Even when he started lecturing to students about his experience, he did not feel any better, but their letters were supportive and encouraging.

At the age of 35, he began suffering from liver and kidney problems due to exposure to radioactive radiation. He was admitted 15 times to the Nagasaki hospital, which was built in 1958 for the victims of the atomic bomb. Later, he contracted stomach cancer and his two brothers also suffered from cancer.

No water, no food

He did not explain how they lived immediately after the explosion, but they may not have. There was no water or food in Nagasaki. The government did not send any, either in the first days after the explosion or afterwards. The survivors who could not escape ate what they could find or what their relatives sent them, if they had any. The northern part of the city was completely destroyed. Those who had nowhere to go settled in underground shelters or built emergency shelters out of wood they found around.

There was no medical assistance. The Faculty of Medicine was destroyed. It was only 600 metres from the site of the explosion. Almost immediately, 900 professors and medical students died. The largest hospital in Nagasaki was also destroyed, so there was no immediate help. Wounds were disinfected with boiled seawater. Late in the afternoon, the army set up a makeshift hospital on the outskirts, but it had few staff and almost no medicines. There were no antibiotics and no blood transfusions. Everything was destroyed, from roads to hospitals and pharmacies.

The destruction made it impossible to reach the worst affected. Those who were exposed to the strongest radiation were charred. They had the misfortune to be exposed at the same time to a lethal dose of radioactivity, thermal radiation and fractures from flying objects.

Those who were within a 1.5 kilometre radius at the time of the explosion had almost no chance of survival. Their bone marrow was destroyed, as was the mucous membrane and the lining of their colon. They died of haemorrhage in less than two months. Most suffered severe burns. As they healed, the skin hardened. Faces were disfigured, bodies too.

No one was allowed to know what they were doing for a living. The Americans feared that if they knew the truth, the Japanese would turn against their occupiers. Years later, it has come to light, but hibakusha notes that even today, too few people are aware of what really happened. They do not accuse the Americans of anything, nor do they hate them. Their lives are too important to them to poison them with hatred, not least because they are aware that, in reality, they were all victims of the war, both Americans and Japanese.